By Ceridwen Dovey

Source: http://www.newyorker.com/culture/cultural-comment/can-reading-make-you-happier?mbid=social_facebook_aud_dev_kwaprsubreadinghappier&kwp_0=140293&kwp_4=619875&kwp_1=321018

No outlet, except maybe to happiness.

Several years ago, I was given as a gift a remote session with a bibliotherapist at the London headquarters of the School of Life, which offers innovative courses to help people deal with the daily emotional challenges of existence. I have to admit that at first I didn’t really like the idea of being given a reading “prescription.” I’ve generally preferred to mimic Virginia Woolf’s passionate commitment to serendipity in my personal reading discoveries, delighting not only in the books themselves but in the randomly meaningful nature of how I came upon them (on the bus after a breakup, in a backpackers’ hostel in Damascus, or in the dark library stacks at graduate school, while browsing instead of studying). I’ve long been wary of the peculiar evangelism of certain readers: You must read this, they say, thrusting a book into your hands with a beatific gleam in their eyes, with no allowance for the fact that books mean different things to people—or different things to the same person—at various points in our lives. I loved John Updike’s stories about the Maples in my twenties, for example, and hate them in my thirties, and I’m not even exactly sure why.

But the session was a gift, and I found myself unexpectedly enjoying the initial questionnaire about my reading habits that the bibliotherapist, Ella Berthoud, sent me. Nobody had ever asked me these questions before, even though reading fiction is and always has been essential to my life. I love to gorge on books over long breaks—I’ll pack more books than clothes, I told Berthoud. I confided my dirty little secret, which is that I don’t like buying or owning books, and always prefer to get them from the library (which, as I am a writer, does not bring me very good book-sales karma). In response to the question “What is preoccupying you at the moment?,” I was surprised by what I wanted to confess: I am worried about having no spiritual resources to shore myself up against the inevitable future grief of losing somebody I love, I wrote. I’m not religious, and I don’t particularly want to be, but I’d like to read more about other people’s reflections on coming to some sort of early, weird form of faith in a “higher being” as an emotional survival tactic. Simply answering the questions made me feel better, lighter.

We had some satisfying back-and-forths over e-mail, with Berthoud digging deeper, asking about my family’s history and my fear of grief, and when she sent the final reading prescription it was filled with gems, none of which I’d previously read. Among the recommendations was “The Guide,” by R. K. Narayan. Berthoud wrote that it was “a lovely story about a man who starts his working life as a tourist guide at a train station in Malgudi, India, but then goes through many other occupations before finding his unexpected destiny as a spiritual guide.” She had picked it because she hoped it might leave me feeling “strangely enlightened.” Another was “The Gospel According to Jesus Christ,” by José Saramago: “Saramago doesn’t reveal his own spiritual stance here but portrays a vivid and compelling version of the story we know so well.” “Henderson the Rain King,” by Saul Bellow, and “Siddhartha,” by Hermann Hesse, were among other prescribed works of fiction, and she included some nonfiction, too, such as “The Case for God,” by Karen Armstrong, and “Sum,” by the neuroscientist David Eagleman, a “short and wonderful book about possible afterlives.”

I worked my way through the books on the list over the next couple of years, at my own pace—interspersed with my own “discoveries”—and while I am fortunate enough to have my ability to withstand terrible grief untested, thus far, some of the insights I gleaned from these books helped me through something entirely different, when, over several months, I endured acute physical pain. The insights themselves are still nebulous, as learning gained through reading fiction often is—but therein lies its power. In a secular age, I suspect that reading fiction is one of the few remaining paths to transcendence, that elusive state in which the distance between the self and the universe shrinks. Reading fiction makes me lose all sense of self, but at the same time makes me feel most uniquely myself. As Woolf, the most fervent of readers, wrote, a book “splits us into two parts as we read,” for “the state of reading consists in the complete elimination of the ego,” while promising “perpetual union” with another mind.

Bibliotherapy is a very broad term for the ancient practice of encouraging reading for therapeutic effect. The first use of the term is usually dated to a jaunty 1916 article in The Atlantic Monthly, “A Literary Clinic.” In it, the author describes stumbling upon a “bibliopathic institute” run by an acquaintance, Bagster, in the basement of his church, from where he dispenses reading recommendations with healing value. “Bibliotherapy is…a new science,” Bagster explains. “A book may be a stimulant or a sedative or an irritant or a soporific. The point is that it must do something to you, and you ought to know what it is. A book may be of the nature of a soothing syrup or it may be of the nature of a mustard plaster.” To a middle-aged client with “opinions partially ossified,” Bagster gives the following prescription: “You must read more novels. Not pleasant stories that make you forget yourself. They must be searching, drastic, stinging, relentless novels.” (George Bernard Shaw is at the top of the list.) Bagster is finally called away to deal with a patient who has “taken an overdose of war literature,” leaving the author to think about the books that “put new life into us and then set the life pulse strong but slow.”

Today, bibliotherapy takes many different forms, from literature courses run for prison inmates to reading circles for elderly people suffering from dementia. Sometimes it can simply mean one-on-one or group sessions for “lapsed” readers who want to find their way back to an enjoyment of books. Berthoud and her longtime friend and fellow bibliotherapist Susan Elderkin mostly practice “affective” bibliotherapy, advocating the restorative power of reading fiction. The two met at Cambridge University as undergraduates, more than twenty years ago, and bonded immediately over the shared contents of their bookshelves, in particular Italo Calvino’s novel “If on a Winter’s Night a Traveller,” which is itself about the nature of reading. As their friendship developed, they began prescribing novels to cure each other’s ailments, such as a broken heart or career uncertainty. “When Suse was having a crisis about her profession—she wanted to be a writer, but was wondering if she could cope with the inevitable rejection—I gave her Don Marquis’s ‘Archy and Mehitabel’ poems,” Berthoud told me. “If Archy the cockroach could be so dedicated to his art as to jump on the typewriter keys in order to write his free-verse poems every night in the New York offices of the Evening Sun, then surely she should be prepared to suffer for her art, too.” Years later, Elderkin gave Berthoud,who wanted to figure out how to balance being a painter and a mother, Patrick Gale’s novel “Notes from an Exhibition,” about a successful but troubled female artist.

They kept recommending novels to each other, and to friends and family, for many years, and, in 2007, when the philosopher Alain de Botton, a fellow Cambridge classmate, was thinking about starting the School of Life, they pitched to him the idea of running a bibliotherapy clinic. “As far as we knew, nobody was doing it in that form at the time,” Berthoud said. “Bibliotherapy, if it existed at all, tended to be based within a more medical context, with an emphasis on self-help books. But we were dedicated to fiction as the ultimate cure because it gives readers a transformational experience.”

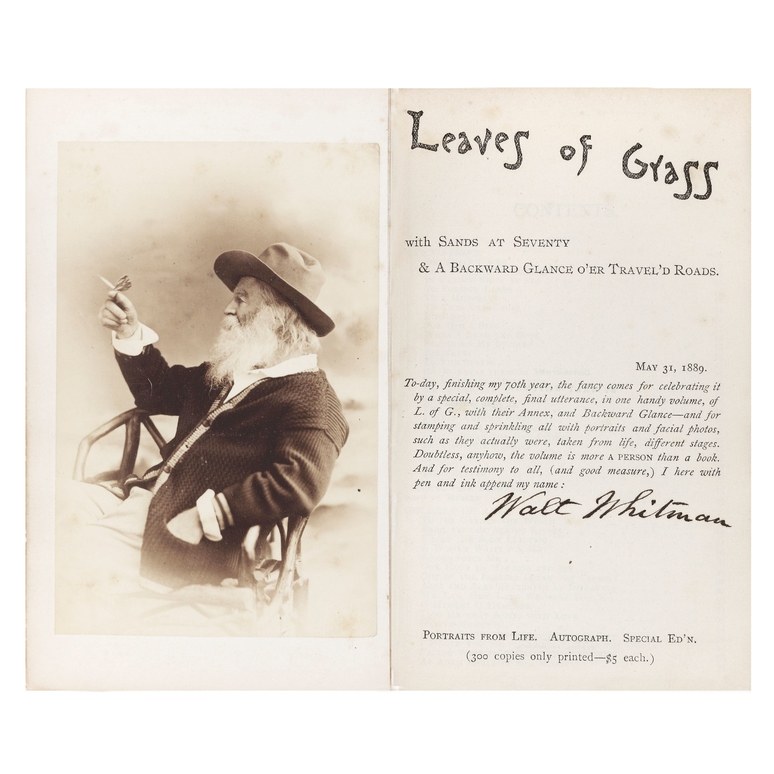

Berthoud and Elderkin trace the method of bibliotherapy all the way back to the Ancient Greeks, “who inscribed above the entrance to a library in Thebes that this was a ‘healing place for the soul.’ “ The practice came into its own at the end of the nineteenth century, when Sigmund Freud began using literature during psychoanalysis sessions. After the First World War, traumatized soldiers returning home from the front were often prescribed a course of reading. “Librarians in the States were given training on how to give books to WWI vets, and there’s a nice story about Jane Austen’s novels being used for bibliotherapeutic purposes at the same time in the U.K.,” Elderkin says. Later in the century, bibliotherapy was used in varying ways in hospitals and libraries, and has more recently been taken up by psychologists, social and aged-care workers, and doctors as a viable mode of therapy.

There is now a network of bibliotherapists selected and trained by Berthoud and Elderkin, and affiliated with the School of Life, working around the world, from New York to Melbourne. The most common ailments people tend to bring to them are the life-juncture transitions, Berthoud says: being stuck in a rut in your career, feeling depressed in your relationship, or suffering bereavement. The bibliotherapists see a lot of retirees, too, who know that they have twenty years of reading ahead of them but perhaps have only previously read crime thrillers, and want to find something new to sustain them. Many seek help adjusting to becoming a parent. “I had a client in New York, a man who was having his first child, and was worried about being responsible for another tiny being,” Berthoud says. “I recommended ‘Room Temperature,’ by Nicholson Baker, which is about a man feeding his baby a bottle and having these meditative thoughts about being a father. And of course ‘To Kill a Mockingbird,’ because Atticus Finch is the ideal father in literature.”

Berthoud and Elderkin are also the authors of “The Novel Cure: An A-Z of Literary Remedies,” which is written in the style of a medical dictionary and matches ailments (“failure, feeling like a”) with suggested reading cures (“The History of Mr. Polly,” by H. G. Wells). First released in the U.K. in 2013, it is now being published in eighteen countries, and, in an interesting twist, the contract allows for a local editor and reading specialist to adapt up to twenty-five per cent of the ailments and reading recommendations to fit each particular country’s readership and include more native writers. The new, adapted ailments are culturally revealing. In the Dutch edition, one of the adapted ailments is “having too high an opinion of your own child”; in the Indian edition, “public urination” and “cricket, obsession with” are included; the Italians introduced “impotence,” “fear of motorways,” and “desire to embalm”; and the Germans added “hating the world” and “hating parties.” Berthoud and Elderkin are now working on a children’s-literature version, “A Spoonful of Stories,” due out in 2016.

For all avid readers who have been self-medicating with great books their entire lives, it comes as no surprise that reading books can be good for your mental health and your relationships with others, but exactly why and how is now becoming clearer, thanks to new research on reading’s effects on the brain. Since the discovery, in the mid-nineties, of “mirror neurons”—neurons that fire in our brains both when we perform an action ourselves and when we see an action performed by someone else—the neuroscience of empathy has become clearer. A 2011 study published in the Annual Review of Psychology, based on analysis of fMRI brain scans of participants, showed that, when people read about an experience, they display stimulation within the same neurological regions as when they go through that experience themselves. We draw on the same brain networks when we’re reading stories and when we’re trying to guess at another person’s feelings.

Other studies published in 2006 and 2009 showed something similar—that people who read a lot of fiction tend to be better at empathizing with others (even after the researchers had accounted for the potential bias that people with greater empathetic tendencies may prefer to read novels). And, in 2013, an influential study published in Science found that reading literary fiction (rather than popular fiction or literary nonfiction) improved participants’ results on tests that measured social perception and empathy, which are crucial to “theory of mind”: the ability to guess with accuracy what another human being might be thinking or feeling, a skill humans only start to develop around the age of four.

Keith Oatley, a novelist and emeritus professor of cognitive psychology at the University of Toronto, has for many years run a research group interested in the psychology of fiction. “We have started to show how identification with fictional characters occurs, how literary art can improve social abilities, how it can move us emotionally, and can prompt changes of selfhood,” he wrote in his 2011 book, “Such Stuff as Dreams: The Psychology of Fiction.” “Fiction is a kind of simulation, one that runs not on computers but on minds: a simulation of selves in their interactions with others in the social world…based in experience, and involving being able to think of possible futures.” This idea echoes a long-held belief among both writers and readers that books are the best kinds of friends; they give us a chance to rehearse for interactions with others in the world, without doing any lasting damage. In his 1905 essay “On Reading,” Marcel Proust puts it nicely: “With books there is no forced sociability. If we pass the evening with those friends—books—it’s because we really want to. When we leave them, we do so with regret and, when we have left them, there are none of those thoughts that spoil friendship: ‘What did they think of us?’—‘Did we make a mistake and say something tactless?’—‘Did they like us?’—nor is there the anxiety of being forgotten because of displacement by someone else.”

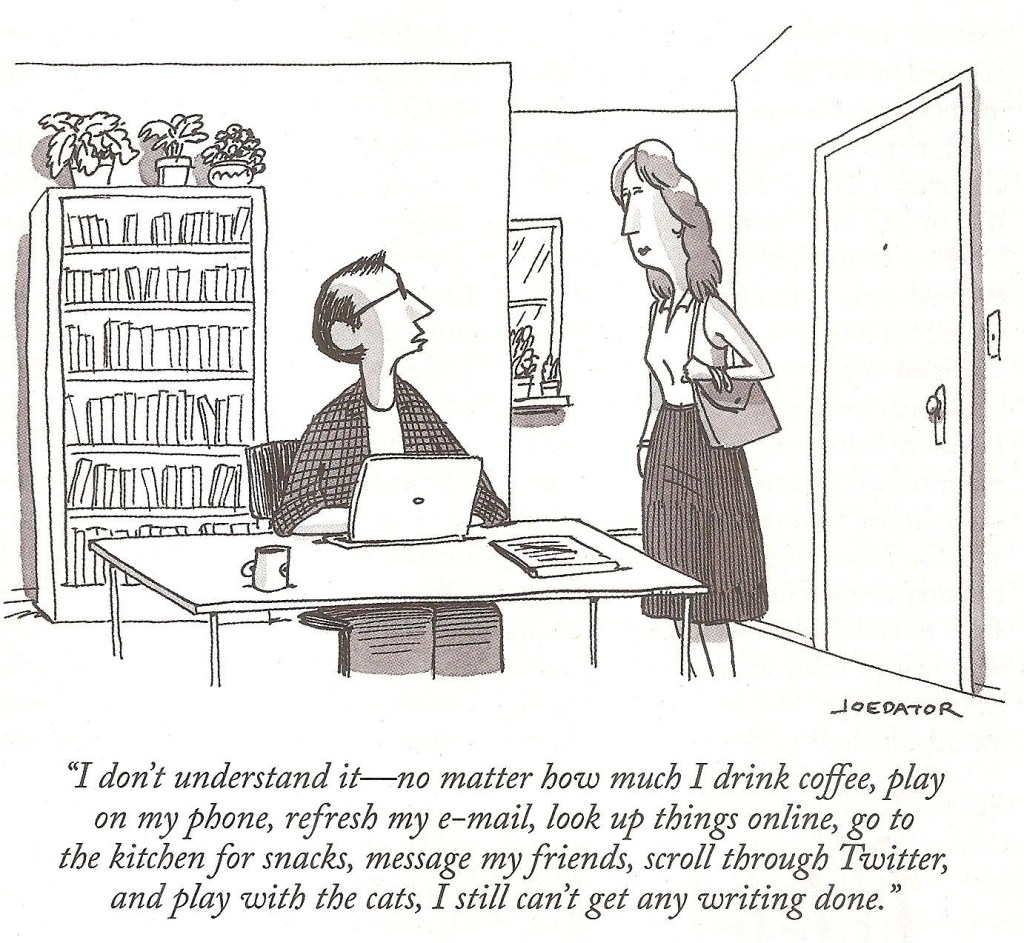

George Eliot, who is rumored to have overcome her grief at losing her life partner through a program of guided reading with a young man who went on to become her husband, believed that “art is the nearest thing to life; it is a mode of amplifying experience and extending our contact with our fellow-men beyond the bounds of our personal lot.” But not everybody agrees with this characterization of fiction reading as having the ability to make us behave better in real life. In her 2007 book, “Empathy and the Novel,” Suzanne Keen takes issue with this “empathy-altruism hypothesis,” and is skeptical about whether empathetic connections made while reading fiction really translate into altruistic, prosocial behavior in the world. She also points out how hard it is to really prove such a hypothesis. “Books can’t make change by themselves—and not everyone feels certain that they ought to,” Keen writes. “As any bookworm knows, readers can also seem antisocial and indolent. Novel reading is not a team sport.” Instead, she urges, we should enjoy what fiction does give us, which is a release from the moral obligation to feel something for invented characters—as you would for a real, live human being in pain or suffering—which paradoxically means readers sometimes “respond with greater empathy to an unreal situation and characters because of the protective fictionality.” And she wholeheartedly supports the personal health benefits of an immersive experience like reading, which “allows a refreshing escape from ordinary, everyday pressures.”

So even if you don’t agree that reading fiction makes us treat others better, it is a way of treating ourselves better. Reading has been shown to put our brains into a pleasurable trance-like state, similar to meditation, and it brings the same health benefits of deep relaxation and inner calm. Regular readers sleep better, have lower stress levels, higher self-esteem, and lower rates of depression than non-readers. “Fiction and poetry are doses, medicines,” the author Jeanette Winterson has written. “What they heal is the rupture reality makes on the imagination.”

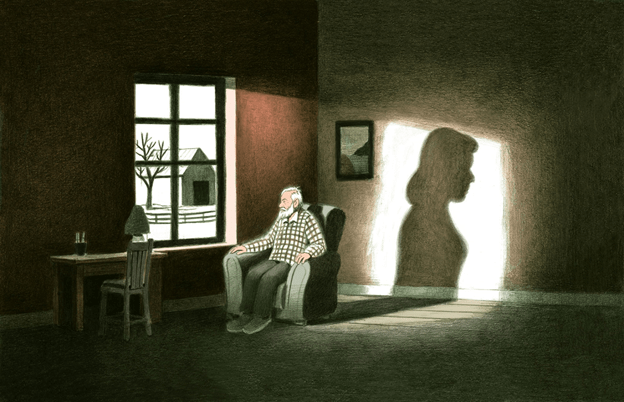

One of Berthoud’s clients described to me how the group and individual sessions she has had with Berthoud have helped her cope with the fallout from a series of calamities, including losing her husband, the end of a five-year engagement, and a heart attack. “I felt my life was without purpose,” she says. “I felt a failure as a woman.” Among the books Berthoud initially prescribed was John Irving’s novel “The Hotel New Hampshire.” “He was a favorite writer of my husband, [whom] I had felt unable to attempt for sentimental reasons.” She was “astounded and very moved” to see it on the list, and though she had avoided reading her husband’s books up until then, she found reading it to be “a very rewarding emotional experience, both in the literature itself and ridding myself of demons.” She also greatly appreciated Berthoud guiding her to Tom Robbins’s novel “Jitterbug Perfume,” which was “a real learning curve for me about prejudice and experimentation.”

One of the ailments listed in “The Novel Cure” is “overwhelmed by the number of books in the world,” and it’s one I suffer from frequently. Elderkin says this is one of the most common woes of modern readers, and that it remains a major motivation for her and Berthoud’s work as bibliotherapists. “We feel that though more books are being published than ever before, people are in fact selecting from a smaller and smaller pool. Look at the reading lists of most book clubs, and you’ll see all the same books, the ones that have been shouted about in the press. If you actually calculate how many books you read in a year—and how many that means you’re likely to read before you die—you’ll start to realize that you need to be highly selective in order to make the most of your reading time.” And the best way to do that? See a bibliotherapist, as soon as you can, and take them up on their invitation, to borrow some lines from Shakespeare’s “Titus Andronicus”: “Come, and take choice of all my library/And so beguile thy sorrow…”

Ceridwen Dovey is the author of the novel “Blood Kin” and the short-story collection “Only the Animals.”