Why crime fiction is leftwing and thrillers are rightwing

Today’s crime novels are overtly critical of the status quo, while the thriller explores the danger of the world turned upside down. And with trust in politicians nonexistent, writers are being listened to as rarely before

Source: http://www.theguardian.com/books/booksblog/2015/apr/01/why-crime-fiction-is-leftwing-and-thrillers-are-rightwing?CMP=share_btn_fb

by Val McDermid

I spent the weekend in Lyon, at a crime writing festival that feted writers from all over the world in exchange for us engaging in panel discussions about thought-provoking and wide-ranging topics. They take crime fiction seriously in France – I was asked questions about geopolitics, and the function of fear. I found myself saying things like “escaping the hegemony of the metropolis” in relation to British crime writing in the 1980s.

What they are also deeply interested in is the place of politics in literature. Over the weekend, there were local elections in France, and a thin murmur of unease ran through many of the off-stage conversations with my French friends and colleagues. They were anxious about the renaissance of the right, of the return of Nicolas Sarkozy, the failure of the left and the creeping rise of the Front National.

As my compatriot Ian Rankin pointed out, the current preoccupations of the crime novel, the roman noir, the krimi lean to the left. It’s critical of the status quo, sometimes overtly, sometimes more subtly. It often gives a voice to characters who are not comfortably established in the world – immigrants, sex workers, the poor, the old. The dispossessed and the people who don’t vote.

The thriller, on the other hand, tends towards the conservative, probably because the threat implicit in the thriller is the world turned upside down, the idea of being stripped of what matters to you. And as Bob Dylan reminds us, “When you ain’t got nothing, you got nothing to lose.”

Of course, these positions don’t usually hit the reader over the head like a party political broadcast. If it is not subtle, all you succeed in doing is turning off readers in their droves. Our views generally slip into our work precisely because they are our views, because they inform our perspective and because they’re how we interpret the world, not because we have any desire to convert our readership to our perspective.

Except, of course, that sometimes we do.

Rest of the article: http://www.theguardian.com/books/booksblog/2015/apr/01/why-crime-fiction-is-leftwing-and-thrillers-are-rightwing?CMP=share_btn_fb

=8888=

A counterpoint:

Thrillers are politically conservative? That’s not right

Val McDermid says that while crime fiction is naturally of the left, thrillers are on the side of the status quo. Jonathan Freedland votes against this reading

Source: http://www.theguardian.com/books/booksblog/2015/apr/03/thrillers-politically-conservative-val-mcdermid-crime-fiction-jonathan-freedland

by Jonathan Freedland

Quickfire quiz. Identify the following as left or right. Big business? On the right, obviously. Trade unions? Left, of course. The one per cent? That’d be the right. Nicola Sturgeon? Clearly, on the left. If those are too easy, try this literary variant. Crime novels: right or left? And what about thrillers: where on the political spectrum do those belong?

Val McDermid, undisputed maestro of crime, reckons she knows the answer. Writing earlier this week, she argued that her own genre was rooted firmly on the left: “It’s critical of the status quo, sometimes overtly, sometimes more subtly. It often gives a voice to characters who are not comfortably established in the world – immigrants, sex workers, the poor, the old. The dispossessed and the people who don’t vote.”. Thrillers, by contrast, are inherently conservative, “probably because the threat implicit in the thriller is the world turned upside down, the idea of being stripped of what matters to you.”

I understand the logic. You can see how McDermid’s own novels, like those of, say, Ian Rankin – another giant in the field, whom she cited as an ally in this new left/right branding exercise – do indeed offer a glimpse into the lives of those too often consigned to the margins, those power would prefer to ignore. But does that really go for all crime writing, always? If it does, someone forgot to tell Miss Marple.

Still, my quibble is not really with McDermid’s claim that the crime novel leans leftward. I want to object to the other half of her case: that the thriller tilts inevitably towards the right. As someone who is both a card-carrying Guardian columnist and a writer of political thrillers, I feel compelled to denounce the very idea.

Sure, there are individual stars of the genre who sit on the right. Tom Clancy was an outspoken Republican (though even his most famous creation, Jack Ryan, was ready to rebel against a bellicose US president for meddling in Latin America). But Clancy’s conservatism is more the exception than the rule.

Consider the supreme master of the spy thriller, John le Carré. His cold war novels stood against the mindless jingoism of the period, resisting the Manichean equation of east-west with evil-good. In the last decade, Le Carré has mercilessly exposed the follies of the war on terror, probing deep into the web of connections that ties together finance, politics and the deep state. The older he gets, the more Le Carré seems to be tearing away at the establishment and its secret, complacently amoral ways.

Rest of the article: http://www.theguardian.com/books/booksblog/2015/apr/03/thrillers-politically-conservative-val-mcdermid-crime-fiction-jonathan-freedland

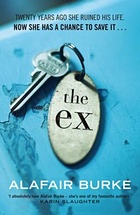

A pleasingly suspenseful mixture of legal thriller and whodunnit, Alafair Burke’s latest novel, The Ex (Faber, £12.99), introduces us to lippy, take-no‑prisoners New York City district attorney Olivia Randall, who receives a panicky phone call from the teenage daughter of her former fiance, Jack Harris, begging for help. Harris, whose wife was killed in a mass shooting three years earlier, has been charged with triple homicide, which the police are treating as a revenge attack because one of the victims is the father of the boy who shot his wife. For Olivia, representing Jack is a way to make up for the hurt she caused him in the past, but his alibi is flimsy and there is corroborating evidence, and she begins to wonder if he may, after all, be guilty. Burke’s writing has always been intelligent and often funny, and her female protagonists sharp and engaging – The Ex is her best yet.

A pleasingly suspenseful mixture of legal thriller and whodunnit, Alafair Burke’s latest novel, The Ex (Faber, £12.99), introduces us to lippy, take-no‑prisoners New York City district attorney Olivia Randall, who receives a panicky phone call from the teenage daughter of her former fiance, Jack Harris, begging for help. Harris, whose wife was killed in a mass shooting three years earlier, has been charged with triple homicide, which the police are treating as a revenge attack because one of the victims is the father of the boy who shot his wife. For Olivia, representing Jack is a way to make up for the hurt she caused him in the past, but his alibi is flimsy and there is corroborating evidence, and she begins to wonder if he may, after all, be guilty. Burke’s writing has always been intelligent and often funny, and her female protagonists sharp and engaging – The Ex is her best yet.