To Alec Burks, a 30-year-old project manager at a construction company in Seattle, Sunday evenings feel like “the end of freedom,” a dreadful period when time feels like it’s quickly disappearing, and, all of a sudden, “in 12 hours, I’m going to be back at my desk.” It’s not that Burks doesn’t like his job—he does. But one thing that contributes to the feeling, he told me, is that “you almost have to shrink who you are a little bit sometimes to fit into that mold of your job description.” The weekend, by contrast, doesn’t require any such shrinking.

The not-exactly-clinical diagnosis for this late-weekend malaise is the Sunday scaries, a term that has risen to prominence in the past decade or so. It is not altogether surprising that the transition from weekend to workweek is, and likely has always been, unpleasant. But despite the fact that the contours of the standard workweek haven’t changed for the better part of a century, there is something distinctly modern about the queasiness so many people feel on Sunday nights about returning to the grind of work or school.

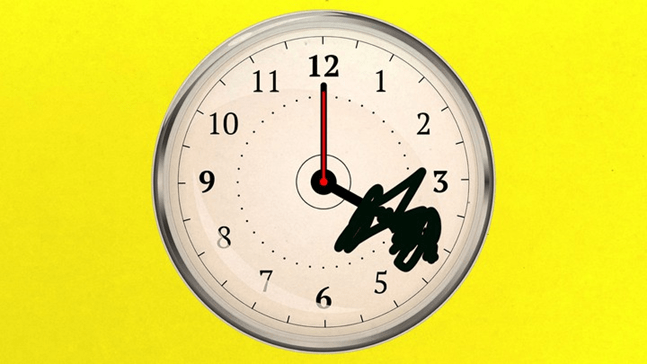

Regardless of whether people call this experience the Sunday scaries (Sunday evening feeling and Sunday syndrome are two alternatives), a lot of them undergo some variation of it. A 2018 survey commissioned by LinkedIn found that 80 percent of working American adults worry about the upcoming workweek on Sundays. Another survey by a home-goods brand found that the Sunday scaries’ average time of arrival is 3:58 p.m., though they seem to set in later than that for many people. (A cousin of the Sunday scaries is the returning-from-vacation scaries, which can fall on any day of the week.)

Read: Workism is making Americans miserable

“This feeling, whether we call it anxiety, worry, stress, fear, whatever, it’s all really the same thing,” says Jonathan Abramowitz, a clinical psychologist and professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “Psychologically, it’s a response to the perception of some sort of threat.” The perceived threat varies—it might be getting up early, or being busy and “on” for several days in a row—but the commonality, Abramowitz says, is that “we jump to conclusions” and “underestimate our ability to cope.” For most people, he reckons, the stress of Sunday is uncomfortable but ultimately manageable—and they end up coping just fine. (And just as with other forms of anxiety, some people don’t feel the Sunday scaries at all.)

“Low-grade existential dread” is how Erin Thibeau, a 28-year-old who works in marketing at a design firm in Brooklyn, describes the feeling she gets on Sunday afternoons and evenings. For her, the end of a weekend presents stressful questions about whether she has taken full advantage of having two days off. Those questions fall under two categories that seem to be in tension: “It’s a mix of ‘Have I been productive enough?’ and ‘Have I relaxed enough?’” she told me.

“In 19—whatever—52, some people hated their jobs and didn’t want to go back to work, but I don’t think this is about hating your job,” says Anne Helen Petersen, a senior culture writer at BuzzFeed and the author of the forthcoming book Can’t Even: How Millennials Became the Burnout Generation. “I think the Sunday scaries are about feeling an overwhelming sense of pressure”—to perform well at work and thus pursue or maintain financial stability, as well as to keep up other everyday responsibilities, like cooking or child care.

“I don’t think there’s anything that’s timeless about [the Sunday scaries],” Petersen told me. “Burnout and the anxiety that accompanies it are so much about living under our current iteration of capitalism and about class insecurity.” From roughly the end of World War II to 1970—a period that’s often called the Golden Age of American capitalism—Petersen says, “there were a ton of jobs that weren’t great, but the difference was that people were more secure in their class position … [Now] it’s this huge combination of not only ‘How am I going to do in my job?,’ but all these other things that I’m anxious about—‘If I lose my job, then I’m not going to have medical insurance.’” This goes some way toward explaining the need to make weekends both productive and relaxing—workers need to both get stuff done and also make sure that they’ve sufficiently recharged to get more stuff done during the week.

Read: ‘Ugh, I’m so busy,’ a status symbol for our time

Work has changed, and so have Sundays themselves. One analysis of Canadian time-use data from 1981 to 2005 that tracked paid work, chores, shopping, and child care found that “Sundays became busier and behaviorally closer to weekdays than they were at the beginning of the 1980s.” “This change would probably become even more obvious,” the study’s author speculated, “if one were to go back to the older data sets, such as [one 1968 data set] from Washington, D.C., where Sunday meals at home occupied more than 90 minutes and shopping only 8 minutes.”

Given how work (side gigs included) has, for many people, bled into nights and weekends, Petersen says, “Two days is not enough—it’s just not … For people I know, myself included, Saturday is a catch-up day, and then Sunday is the only real day of leisure. So people, as soon as they start, they’re like, ‘It’s about to end!’ You’re so conscious of the fact that it’s so short.”

This is the economic milieu from which the Sunday scaries have emerged. It is responsible for the Sunday scaries–branded vegan CBD gummies, the how-to videos outlining “productive” Sunday routines for preparing for the workweek, and—perhaps most troublingly—the tweets from brands such as Starbucks, Mary Kay, and Malibu Rum about warding off the Sunday scaries.

The phrase itself hasn’t been around for very long. Kory Stamper, a lexicographer and author, told me that the first written usage of Sunday scaries she could find after searching around was in a hangover-inspired entry from 2009 on the website Urban Dictionary. Over the course of the 2010s, though, the scaries became less about the consequences of partying than the anticipation of the week ahead. A spokesperson for Twitter told me that use of the phrase has been “growing steadily” on its platform since early 2016, and that 90 percent of tweets that mention it come from people in the U.S.

One advantage of the term is that it is immediately graspable, but at the same time it is almost gratingly infantilizing, expressing genuinely uncomfortable emotions in the language of toddlers. (Multiple people I interviewed for this story disliked the term on these grounds, even as they noted its usefulness.)

“For some reason, we have a great whack of words that sound silly but describe unpleasant feelings or negative emotions: the heebie-jeebies, the screaming meemies, the collywobbles, the jitters, the creeps, a case of the Mondays, boo-hoo,” Stamper says. She notes that some of these terms are playful and sonically repetitive, and wondered if “we like these ameliorating terms because their humor makes it easier to talk about something we would rather not talk about at all.”

The phrase seems even more modern, and even more childish, considering the dangerous outcomes that many American workers used to fear on the job. “There are lots of stories, almost 100 years ago, of people dreading going back to the factory, whether it’s injuries or being yelled at,” says Nelson Lichtenstein, a professor of history at the University of California at Santa Barbara. “It was said that at the Ford Motor Company, the foreman knew how to shout ‘Speed up!’ in 15 languages.” Scaries doesn’t quite do justice to the awful work experiences that many people had back then, and still have today.

Whatever this feeling is called, and whatever economic conditions may be in place right now, people have probably been mourning the end of weekends in one way or another for as long as days off have existed. In the mid-19th century, when Sunday was workers’ only official full day off in England, many of them extended their break by skipping work on Monday, “whether to relax, to recover from drunkenness, or both,” explained Witold Rybczynski in The Atlantic in 1991. This habit, which scans as a symptom of a Sunday scaries–like feeling, was effectively formalized in some industries and was referred to as “keeping Saint Monday.”

Precursors to the modern Sunday scaries were detectable as long as 30 years ago. In 1991, The New York Times published an analysis of “the Sunday blues,” and while economic precarity was listed among the potential causes, the article presented a host of other possible explanations: an interruption of the internal biological clock’s usual weekday sleep cycles, caffeine withdrawal, hangovers, and, of course, a simple dislike of work (or school, or housework).

The proposed cures for this unease range from the micro to the macro. Some of the people I interviewed who experience the Sunday scaries have been implementing plans to thwart them. Erin Thibeau finds some success with what she calls her “Sunday Funday initiative”—a program that aims to “extend the feeling of the weekend” by strategically scheduling movies, museum visits, and walks in the park when the scaries typically set in. Maggie Lofboom, a 36-year-old who works in landscape design and as an opera singer in Minneapolis, says she cross-stitches and takes baths to keep the scaries at bay.

Sarah Savoy, a 35-year-old who works at a think tank in Washington, D.C., stumbled on an unexpected antidote: having young children. She used to get the Sunday scaries in her 20s, but they’ve since subsided. “Our older daughter is a terrible napper, so [on Sundays] from 2 o’clock on it’s survival parenting, just trying to get to the end of the day,” she told me. “One of the things I look forward to about the week is that we have a pretty set routine, which can fall apart on a weekend.” Of course, this pattern has produced its own weekly emotional cycle, with a feeling of stress that crests on Saturday mornings, when Savoy makes a household to-do list for the weekend.

Jonathan Abramowitz, the psychology professor, says that the most reliable way to banish the Sunday scaries, especially if they have escalated to the point of being debilitating, is to practice cognitive behavioral therapy, a means of revising mental and behavioral patterns that can be learned from a therapist, an app, or a workbook. “In the short term,” he says, “exercising, taking a walk, or doing some activity that you really enjoy on Sunday can take your mind off the scaries temporarily.”

When I asked Anne Helen Petersen what would cure the Sunday scaries, she laughed and gave a two-word answer: “Fix capitalism.” “You have to get rid of the conditions that are creating precarity,” she says. “People wouldn’t think that universal health care has anything to do with the Sunday scaries, but it absolutely does … Creating a slightly different Sunday routine isn’t going to change the massive structural problems.”

One potential system-wide change she has researched—smaller than implementing universal health care, but still big—is a switch to a four-day workweek. “When people had that one more day of leisure, it opened up so many different possibilities to do the things you actually want to do and to actually feel restored,” she says.

As a haver of the Sunday scaries myself, I would like to live in a world where there’s less to fear about Monday. At the same time, I suspect that there is an element of tragedy inextricable from the basic nature of weekends, which (not to get too glum about it) are like lives in miniature: That approaching expanse of leisure that one can survey on Friday evenings, no matter how well used, is followed within 48 hours by the distressing realization that the end of it is inevitable, and that what once seemed like so much time has been used up. On Sundays, we each reckon with the passing of time and die a small death. And that’s scary.