by Ben Blatt

The first literary mystery to be solved by numbers was a 150-year-old whodunit finally put to rest in 1963. Two statistics professors learned of the long-running debate over a dozen contested essays from The Federalist Papers, and they saw that they might succeed where historians had failed. Both Alexander Hamilton and James Madison claimed to have written the same 12 essays, but who was right?

The answer lay in how each writer used hundreds of small words like but and what, which altogether formed a kind of literary fingerprint. The statisticians painstakingly cut up each essay and counted the words by hand—a process during which “a deep breath created a storm of confetti and a permanent enemy.” And by comparing hundreds of word frequencies, they came up with a clear answer after so many years of speculation: the contested essays were distinctly the work of James Madison.

Since 1963, similar methods have continued to yield major findings. Take, for instance, last year’s revelation that Shakespeare collaborated with Christopher Marlowe. And in the meantime, the technology involved has leapt from scissors and paper to computer and code, giving rise to a whole new field of study—the digital humanities.

In my new book, Nabokov’s Favorite Word is Mauve, I use simple data to whiz through hundreds of classics, bestsellers, and fan fiction novels to explore anew our favorite authors and how they write. I uncover everything from literary fingerprints and favorite words and tics, to the changing reading level of NYT bestsellers and how men and women write characters differently.

If you have a body of literature, stats can now serve as an x-ray. Here are a few fascinating examples from Nabokov’s Favorite Word is Mauve:

Writing Advice

There is a lot of writing advice out there. But it’s hard to test, and it’s often best to judge someone not by what they say but what they do. Novelists may tell their adoring fans to do one thing, but do they actually follow their own advice? With data, we can find out—looking at everything from the overuse of adverbs to Strunk and White’s advice against qualifiers like “very” or “pretty.”

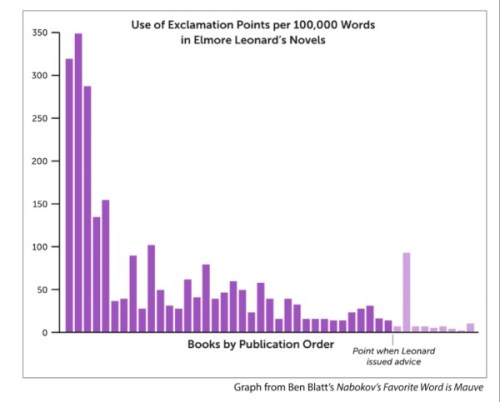

One of my favorite examples comes from Elmore Leonard’s 10 Rules of Writing, where Leonard offers the following rule about exclamation points: “You are allowed no more than two or three per 100,000 words of prose.” A writing rule in the form of a ratio is a blessing for a statistician, so I ran with it. Does Leonard practice what he preaches?

From a strict numerical view, no. Leonard wrote over 40 novels which totaled 3.4 million words. If he were to follow his own advice he should have been allowed only 102 exclamation points his entire career. In practice, he used 1,651—which is 16 times as many as he recommends.

But looking deeper, we find that Leonard did follow the spirit of his own rule. Below are 50 novelists, representing a range of classic authors and bestselling authors. Elmore Leonard beats out everyone.

And the picture gets even more interesting when we look at how Leonard’s use changes over time. The chart below shows the number of exclamation points that Leonard used in each one of his novels from the start of the career. He loved the exclamation point as a novice, but he slowly weaned off of it over time.

Interestingly, after he delivered his exclamation point rule in 10 Rules for Writing, his use decreased even further (the one exception was Leonard’s sole children’s novel). He may have been a zealot: no one I looked at uses exclamation points at a rate lower than two or three per 100,000. But Leonard practiced what he preached: he got closer to his magic ratio than any other writer, especially in his final stretch of novels.

He was also on to something. I parsed through thousands of amateur fan-fiction stories online and found they were not only enthusiastic about their story universes, but for exclamation points as well. The average published author relies on about 1/4th as many exclamation points as the average amateur writer.

How Cliché

The book world loves a good list: bestsellers, award winners, “best of the year” lists. But what other superlative lists are there to uncover out there in the literary world? In Nabokov’s Favorite Word is Mauve, I decided to ask: who uses the shortest sentences, the most adverbs, writes at the lowest grade level or relies on the most clichés?

I took all expressions mentioned in the 2013 book by Christine Ammer titled The Dictionary of Clichés. These are phrases like “fish out of water,” “dressed to kill,” and “not one’s cup of tea”—4,000 phrases in total. To my knowledge, Ammer’s book is the largest collection of English language clichés. I then scanned through the complete bibliographies of the same 50 authors mentioned above to see who used the most clichés.

The answer: James Patterson.

You’d expect some recency bias in the dictionary of clichés (Jane Austen’s characters, unfortunately, weren’t ever described as “dressed to kill”). So I also looked at every single book that ranked on Publishers Weekly’s bestselling books of the year since 2000. James Patterson can’t blame his time period alone. Even compared to his contemporaries in genre and time, Patterson comes in with five of the 10 most clichéd books. He’s clearly making it work, though. Of those PW lists, Patterson has 16 books, more titles than any other writer.

Start with a Bang

In response to a question on Twitter about her favorite first sentence in literature, novelist Margaret Atwood answered: Call me Ishmael. “Three words. Power-packed. Why Ishmael? It’s not his real name. Who’s he speaking to? Eh?”

Atwood emphasized the brevity of the Moby-Dick opener, and she is similarly concise in her own work. I compared the median length of her opening sentence to that of the 50 authors in the exclamation point chart above. Only one author, Toni Morrison, beats her out.

Opening sentences are far from an exact science, but keeping them short and powerful by rule of thumb is a smart place to start. Drawing from a range of sources, I assembled a list of the consensus top 20 opening sentences in literature. And of that list, 60% of the openers are short when compared to the book’s average sentence length.

But when you look a much wider sample of literature, most authors in practice opt for long openers. In 69% of all of the books I looked at, the opening sentence is longer than the average sentence throughout the rest of the book. It might be that authors like Toni Morrison and Margaret Atwood are on to something as they keep their openers “power-packed.”

Beach Weather

In one last example, let’s return to Elmore Leonard’s 10 Rules of Writing. His first rule (#1!) is “Never open a book with weather.” Apparently Leonard had strong feelings about this trope, but anyone who’s ever heard too many plays on the old saw, “it was a dark and stormy night,” will know where he’s coming from.

Leonard again lives up to his own advice. But there’s one author who completely flouts it, and it’s an example I love.

Danielle Steel, known for selling hundreds of millions of books, should also be known for talking about the weather. She started her first book off “It was a gloriously sunny day and the call from Carson Advertising came at nine-fifteen.” She’s never looked back.

Nearly half her of introductions involve weather—mostly benign, positive weather (“perfect deliciously warm Saturday afternoons,” “perfect balmy May evening”, “absolutely perfect June day,” or simply: “The weather was magnificent.”). But like Patterson she has made her rule-breaking choice work. It’s a distinctive style that’s all her own—and it’s a quirk that at least this reader would never have been able to pin down without having been able to run the numbers first.

J.K. Rowling’s Twitter feud with Trump supporters is so bad she’s now fighting some of her fans – The Washington Post

Rowling’s brushes with political controversy are nothing new. She’s just more open about her views now.

Source: J.K. Rowling’s Twitter feud with Trump supporters is so bad she’s now fighting some of her fans – The Washington Post

If there’s any doubt left that we live in divisive political times, know this: Some fans of Harry Potter are burning their copies of the books to protest author J.K. Rowling’s views of the U.S. president. And she’s fighting back on Twitter, insulting those very fans.

That’s right, one of the most beloved series of books in modern history has now become a political prop. Is nothing safe?

Rowling has been vocal about her feelings concerning President Trump for some time. She has mostly used Trump’s favorite platform, Twitter, to share her criticisms.

These tweets have generated a Facebook page’s worth of headlines. But Rowling’s brushes with political controversy are nothing new.

Rowling is a dedicated progressive. She’s a strong believer in welfare, which she relied on during a particularly rough period in her life. As she said during a 2008 Harvard commencement speech, “An exceptionally short-lived marriage had imploded, and I was jobless, a lone parent, and as poor as it is possible to be in modern Britain, without being homeless … By every usual standard, I was the biggest failure I knew.”

More recently, Rowling found herself in the midst of a Twitter battle surrounding Britain’s decision to leave the European Union, referred to as Brexit, which she staunchly opposed.

Much of this now seemingly endless debate was absent during the height of the Harry Potter craze because the author didn’t publicly discuss her views until the publication of the final book in the series. In 2008, a year after “Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows” hit bookshelves, Rowling gave 1 million pounds to Britain’s Labour Party.

That same year, speaking to El Pais, she said of the U.S. presidential campaign in which Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama were battling for the Democratic nomination: “I want a Democrat in the White House. It seems a pity that Clinton and Obama have to be rivals, because both are extraordinary.”

Anyone who gave the Harry Potter books a close reading likely wouldn’t have been surprised by Rowling’s politics.

Most of the subplots involve the triumph of marginalized peoples, be it the mixed-heritage Hermione, a “mudbl–d,” the poverty-stricken Weasleys, the stigmatized Hagrid (essentially an ex-offender reintroduced to society who can no longer practice magic as a result) or the “lower class” house elf named Dobby (the most obvious analogue to American slavery).

Harry himself, after all, was an orphan and survivor of attempted infanticide.

In his book “Harry Potter and the Millennials,” Anthony Gierzynski wrote that, “the evidence indicates that Harry Potter fans are more open to diversity and are more politically tolerant than nonfans; fans are also less authoritarian, less likely to support the use of deadly force or torture, more politically active, and more likely to have had a negative view of the Bush administration.”

Rowling invites anyone to challenge her.

Once Rowling opened up about her beliefs, it has been a steady stream ever since. And while attacking her own fans might seem like a poor marketing choice, it’s important to note one of the values that Rowling holds most dear: freedom of speech.

“Intolerance of alternative viewpoints is spreading to places that make me, a moderate and a liberal, most uncomfortable. Only last year, we saw an online petition to ban Donald Trump from entry to the U.K. It garnered half a million signatures,” she said during the 2016 PEN America Literary Gala at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. “I find almost everything that Mr. Trump says objectionable. I consider him offensive and bigoted. But he has my full support to come to my country and be offensive and bigoted there. His freedom to speak protects my freedom to call him a bigot. His freedom guarantees mine.”

Rowling had already faced some conflict before she publicly expressed her political views. Her Harry Potter books were maligned by some Christian groups, making it one of the most challenged books in 2000, as tracked by the American Library Association’s Office for Intellectual Freedom, according to the New York Times.

“The challenges seem to be objecting to occult or supernatural content in the books and are being made largely by traditional Christians who believe the Bible is a literal document,” Virginia Walter, president of the ALA’s Association for Library Service to Children, told the newspaper. “Any exposure to witches or wizards shown in a positive light is anathema to them. Many of these people feel that the books are door-openers to topics that desensitize children to very real evils in the world.”

The outcry didn’t come only from fringe, radical sects of Christianity, either. As noted in the Christian Post, when Pope Benedict XVI was still Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger he condemned the books for their “subtle seductions, which act unnoticed … deeply distort Christianity in the soul before it can grow properly.”

There’s a certain irony to this, considering Rowling has said that Christianity was a great inspiration for the books.

“To me [the religious parallels have] always been obvious,” she said at a 2007 news conference. “But I never wanted to talk too openly about it because I thought it might show people who just wanted the story where we were going.”

There were Christian references throughout the series. When Harry visits his parents’ graves in one book, the headstone reads, “The last enemy that shall be destroyed is death” — an abridged version of 1 Corinthians 15:26.

The graveyard is also the final resting place of headmaster Albus Dumbledore’s mother and sister, whose tombstone bears the inscription, “Where your treasure is, there your heart be also” — a direct quote from Matthew 6:19.

“I think those two particular quotations he finds on the tombstones at Godric’s Hollow, they sum up — they almost epitomize the whole series,” Rowling said at the news conference.

Share this:

Leave a comment

Filed under 2017, author commentary

Tagged as fan feud, J.K. Rowling, Sunday, The Washington Post, Trump