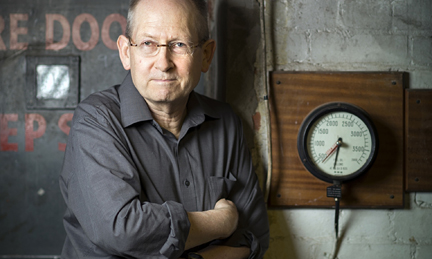

With just fourteen short stories and a novella, the author behind the recent film “Arrival” has gained a rapturous following within the genre and beyond.

Source: Ted Chiang’s Soulful Science Fiction – The New Yorker

by Joshua Rothman

In the early nineteen-nineties, a few occurrences sparked something in Ted Chiang’s mind. He attended a one-man show in Seattle, where he lives, about a woman’s death from cancer. A little later, a friend had a baby and told Chiang about recognizing her son from his movements in the womb. Chiang thought back to certain physical principles he had learned about in high school, in Port Jefferson, New York, having to do with the nature of time. The idea for a story emerged, about accepting the arrival of the inevitable. A linguist, Chiang thought, might learn such acceptance by deciphering the language of an alien race with a different conception of time. For five years, when he wasn’t working as a technical writer in the software industry, Chiang read books about linguistics. In 1998, he published “Story of Your Life,” in a science-fiction anthology series called Starlight. It was around sixty pages long and won three major science-fiction prizes: the Nebula, the Theodore Sturgeon, and the Seiun, which is bestowed by the Federation of Science Fiction Fan Groups of Japan. Last year, “Arrival” was released, an adaptation of “Story of Your Life,” in which Amy Adams plays a linguist who learns, decades in advance, that her daughter will die, as a young woman, of a terminal illness, but goes ahead with the pregnancy anyway.

Chiang is now forty-nine, with streaks of gray in his ponytail. He started writing science fiction in high school. Since then, he has published fourteen short stories and a novella. By this means, he has become one of the most influential science-fiction writers of his generation. He has won twenty-seven major sci-fi awards; he might have won a twenty-eighth if, a few years ago, he hadn’t declined a nomination because he felt that the nominated story, “Liking What You See: A Documentary,” was unfinished. (It imagines using neuroscience to eliminate “lookism,” or the preference for beautiful faces.) Many of Chiang’s stories take place in the past, not the future. His first published story, “Tower of Babylon,” which appeared in 1990 and won a Nebula Award, follows Hillalum, a Babylonian stonecutter tasked with climbing to the top of the world and carving a doorway into its granite ceiling. It has the structure of a parable and an uncanny and uncompromising material concreteness. At the top of the tower, Hillalum finds that the roof of the world is cold and smooth to the touch. The stonecutters are eager to find out what lies on the other side of the sky, but they are also afraid, and, in a prayer service, Chiang writes, “they gave thanks that they were permitted to see so much, and begged forgiveness for their desire to see more.” Chiang goes to great lengths to show how ancient stonecutting techniques might actually be used to breach the floor of Heaven. He writes the science fiction that would have existed in an earlier era, had science existed then.

Chiang’s stories conjure a celestial feeling of atemporality. “Hell Is the Absence of God” is set in a version of the present in which Old Testament religion is tangible, rather than imaginary: Hell is visible through cracks in the ground, angels appear amid lightning storms, and the souls of the good are plainly visible as they ascend to Heaven. Neil, the protagonist, had a wife who was killed during an angelic visitation—a curtain of flame surrounding the angel Nathanael shattered a café window, showering her with glass. (Other, luckier bystanders were cured of cancer or inspired by God’s love.) Attending a support group for people who have lost loved ones in similar circumstances, he finds that, although they are all angry at God, some still yearn to love him so that they can join their dead spouses and children in Heaven. To write this retelling of the Book of Job, in which one might predict an angel’s movements using a kind of meteorology, Chiang immersed himself in the literature of angels and the problem of innocent suffering; he read C. S. Lewis and the evangelical author Joni Eareckson Tada. Since the story was published, in 2001, readers have argued about the meaning of Chiang’s vision of a world without faith, in which the certain and proven existence of God is troubling, rather than reassuring.

Earlier this winter, I began talking with Chiang about his work, first through Skype, then over the phone and via e-mail. He still works as a technical writer—he creates reference materials for programmers—and lives in Bellevue, near Seattle. “I’m curious about what you might call discredited world views,” he told me, during a phone conversation. “It can be tempting to dismiss people from the past—to say, ‘Weren’t they foolish for thinking things worked that way?’ But they weren’t dummies. They came up with theories as to how the universe worked based on the observations available to them at the time. They thought about the implications of things in the ways that we do now. Sometimes I think, What if further observation had confirmed their initial theories instead of disproving them? What if the universe had really worked that way?”

Chiang has been described as a writer of “humanist” sci-fi; many readers feel that his stories are unusually moving and wonder, given their matter-of-fact tone, where their emotional power comes from. His story “The Great Silence” was included in last year’s edition of “The Best American Short Stories,” and Junot Díaz, who edited that volume, has said that Chiang’s “Stories of Your Life and Others” is “as perfect a collection of stories as I’ve ever read.” Chiang himself seems to find this kind of praise bewildering. When, after about a month of long-distance conversation—he is a slow, careful speaker, and so I had asked to interview him again and again—we met for lunch at a ramen restaurant in Bellevue, I asked Chiang why he thought his stories were beloved. He threw up his hands and laughed with genuine incredulity. He had “no idea” how to account for his own success, he said. He seems almost to regard his stories as research projects pursued for their own sake. When I asked him to speculate—surely all writers have some sense of why they are valued?—he blushed and declined.

Chiang was born on Long Island in 1967. He went to Brown and majored in computer science. In 1989, he attended the Clarion Workshop, a kind of Bread Loaf for sci-fi and fantasy writers. Around that time, he moved to Seattle, where he met Marcia Glover, his long-term partner, during a stint at Microsoft (“I was documenting class libraries or A.P.I.s,” he said); she’s an interface designer turned photographer. He admires the writing of Annie Dillard and enjoyed “The Last Samurai,” by Helen DeWitt.

Beyond this narrow Wikipedian territory, Chiang is reluctant to venture. Although he is amiable and warm, he is also reticent and does not riff. Over several conversations, I learned, in addition, that he owns four cats, goes to the gym three times a week, and regards a small cylindrical seal made of hematite sometime around 1200 B.C. as one of his most treasured possessions—it was a gift from his sister, a reference to “Tower of Babylon.” He told me that, when he was a child, his family celebrated Christmas but wasn’t religious. When I asked Chiang if he had hobbies, he said no, and then, after a long pause, admitted that he plays video games. He refused to say what he eats for breakfast. Eventually, I sent him an e-mail with twenty-four questions that, I hoped, might elicit more personal details:

Do you have a favorite novel?

There isn’t one that I would want to single out as a favorite. I’m wary of the idea of a favorite anything.

You’ve spent many years living near the water. Do you like the sea?

Not particularly. I don’t actually spend much time on the coast; it’s just chance that I happened to move here.

What was the last work of art that made you cry?

Don’t know.

Do you consider yourself a sensitive person?

Yes.

What Chiang really wanted to talk about was science fiction. We spoke about free will (“I believe that the universe is deterministic, but that the most meaningful definition of free will is compatible with determinism”), the literary tradition of naturalism (“a fundamentally science-fictional approach of trying to work out the logical consequences of an idea”), time travel (he thinks of “A Christmas Carol” as the first time-travel story), and the metaphorical and political incoherence of Neill Blomkamp’s aliens-under-apartheid movie “District 9” (he believes that “Alien Nation,” in which the aliens are framed as immigrants, is more rigorously thought through). Chiang reframes questions before answering them, making fine philosophical distinctions. He talks more about concepts than he does about people. “I do want there to be a depth of human feeling in my work, but that’s not my primary goal as a writer,” he said, over lunch. “My primary goal has to do with engaging in philosophical questions and thought experiments, trying to work out the consequences of certain ideas.”

Chiang’s novella, “The Lifecycle of Software Objects,” grew, he said, out of his intellectual skepticism about how artificial intelligence is imagined in science fiction. Often, such computers are super-competent servants born in a lab and preprogrammed by engineers. “But what makes any human being a good, reliable worker?” he asked me. “A hundred thousand hours of good parenting, of unpaid emotional labor. That’s the kind of investment on which the business world places no value; it’s an investment made by people who do it out of love.” “Lifecycle” tells of Ana and Derek, two friends who, almost by accident, become the loving and protective parents of artificially intelligent computer programs. Ana and Derek spend decades raising their virtual children, and, by means of a “slow, difficult, and very fraught process”—playing, teaching, chiding, comforting—succeed in creating artificial beings with fully realized selves. Having done so, they are loath to sell their children, or copies of them, to the Silicon Valley startups that are eager to monetize them. They face, instead, the unexpected challenges of virtual parenthood: What do you do when the operating system on which your child runs becomes obsolete? How can you understand the needs and wants of a child so different from yourself?

In an e-mail, I asked Chiang to tell me about his own parents. (He has no children.) Did they inspire the ones in his novella? “I’m not going to try to describe their personalities,” he wrote, “but here are some basic facts”:

Both of my parents were born in mainland China. Their families fled to Taiwan during the Communist Revolution. They went to college in Taiwan and came to the U.S. for their graduate studies; they met here. They’re divorced. My father still works as a professor in the engineering department at SUNY Stony Brook. My mother is retired, but used to be a librarian. I didn’t have them in mind when writing “Lifecycle.”

Perhaps there’s something contrarian in Chiang’s refusal to acknowledge, or even describe, the role that his life plays in the construction of his fiction. Alternatively, he may be being accurate. Contemplating his e-mail, I found myself thinking, in a Chiangian way, about the nature of ethics. According to one theory, a system of ethics flows from the bottom up, emerging from the network of agreements we make in everyday life. According to another, it flows from the top down, and consists of absolute moral truths that are discoverable through rigorous analysis. The feelings in Chiang’s stories are discovered from the top down. “The Lifecycle of Software Objects” isn’t a story about Chiang’s parents disguised as a thought experiment. It’s a thought experiment so thorough that it tells us something about the feeling of parenthood. That kind of thoroughness is unusual. It is, in itself, a labor of love.

“I don’t get that many ideas for stories,” Chiang said, around a decade ago, in an interview with the sci-fi magazine Interzone. “If I had more ideas, I would write them, but unfortunately they only come at long intervals. I’m probably best described as an occasional writer.” That is still more or less true. Chiang continues to make ends meet through technical writing; it’s unclear whether the success of “Arrival” could change that, or even whether he would desire such a change. A script based on another of his stories, “Understand,” is also in development. “I don’t want to try to force myself to write novels in order to make a living,” Chiang wrote, in an e-mail. “I’m perfectly happy writing short stories at my own pace.”

In the course of our conversations, he and I discussed various theories about his writing—about what, in general, his project might be. At lunch, he proffered one theory—that his stories were an attempt to resist “the identification of materialism with nihilism.” Over the phone, I suggested another, perhaps related theory—that Chiang’s stories are about the costs and uses of knowledge. I pointed out that some of his stories are about the pain of knowing too much, while others are about the long path to knowing, which permits of no shortcuts. In “Story of Your Life,” Chiang’s linguist, Louise, finds that knowing your life story in advance doesn’t make you want to change it; if anything, it makes you more determined to live it out in full. Knowledge alone is flat and lifeless; it becomes meaningful through the accumulation of experience over time.

Chiang, in his precise and affable way, questioned my idea that his stories were “about” knowledge. “Is that really a useful way to characterize my stories, as opposed to other people’s stories?” he asked. He laughed—and then suggested a different subject that, he’d noticed, was a “recurring concern” in his work. “There’s a book by Umberto Eco called ‘The Search for the Perfect Language,’ ” he said. “It’s a history of the idea that there could be a language which is perfectly unambiguous and can perfectly describe everything. At one point, it was believed that this was the language spoken by angels in Heaven, or the language spoken by Adam in Eden. Later on, there were attempts by philosophers to create a perfect language.” There’s no such thing, Chiang said, but the idea appealed to him in an abstract way. In “Understand,” he pointed out, the protagonist learns to reprogram his own mind. He knits together the vocabularies of science and art, memory and prediction, literature and math, physics and emotion. “He’s searching for the perfect language, a cognitive language in which he can think,” Chiang said. “A language that will let him think the kinds of thoughts he wants.”