How Do You Like Your Science Fiction? Ten Authors Weigh In On ‘Hard’ vs. ‘Soft’ SF

by Fran Wilde

Source: http://www.tor.com/2016/01/21/how-do-you-like-your-science-fiction-ten-authors-weigh-in-on-hard-vs-soft-sf/

With The Martian a big-screen success and Star Wars: The Force Awakens blowing box office doors off their hinges, articles like this one from NPR have begun appearing all over, encouraging SF authors and readers to “Get Real.” Meanwhile, debates about whether one movie or another is scientific enough are cropping up in various corners of the internet. (This, in my view, feels like an odd ranking system—if one movie has a sarlacc pit as an ancestor, and another might be seen as channeling Ghost [1990, the one with Demi Moore] as a way to explain cross-universe communication via physics… it’s pretty cool, yes? It’s fun to let imaginations wander about? Yes. I’ll be seeing you in the comments, yes. Onwards.)

2001: A Space Odyssey, an example of “hard” science fiction.

So is a deeper, harder line being drawn in the sand about “hard” science fiction than usual? Or are we discovering that perhaps there’s a whole lot more sand available with regards to how imaginative and future-looking fiction can develop, and even entertaining the possibility that these developments could become blueprints for future-fact?

I asked ten science fiction authors about their definitions of “hard” and “soft” science fiction, and how they see science fiction (hard, soft, and otherwise) in today’s terms. They returned with ten fascinating—and not surprisingly, entirely different—answers.

Have a read and then maybe jump in the comments to discuss!

Nancy Kress

Nancy Kress’s latest work is The Best of Nancy Kress (Subterranean Press, 2015).

“Hard SF” and “soft SF” are really both misnomers (although useful in their way). Hard SF has several varieties, starting with really hard, which does not deviate in any way from known scientific principles in inventing the future; this is also called by some “mundane SF.” However, even the hardest SF involves some speculation or else it would not be science fiction.

High-viscosity SF takes some guesses about where current science might go IF certain discoveries are made (such as, for instance, identifying exactly which genes control things like intelligence, plus the ability to manipulate them). Or, alternately, it starts with one implausibility but develops everything else realistically from there (as in Andy Weir’s The Martian, with its huge-velocity windstorm on Mars). From there you go along a continuum toward things that, with our current level of knowledge, do not seem possible, such as faster-than-light travel. At some point along that continuum, high-viscosity SF becomes science fantasy, and then fantasy, when magic is involved. But the critical point is that it IS a continuum, and where a given innovation belongs on it is always a matter of dispute. This is good, because otherwise half the panels at SF cons would have nothing to argue about.

I would define “soft SF” as stories in which SF tropes are used as metaphors rather than literals. For example, aliens that don’t differ from us much in what they can breathe, drink, eat, or how their tech functions. They have no delineated alien planet in the story, because they are meant to represent “the other,” not a specific scientifically plausible creature from an exosolar environment. This seems to me a perfectly valid form of science fiction (see my story “People Like Us”), but it is definitely not “hard SF,” no matter how much fanciful handwaving the author does. Nor are clones who are telepathic or evil just because they’re clones (it’s delayed twinning, is all) or nanotech that can create magical effects (as in the dreadful movie Transcendence).

Tade Thompson

Tade Thompson’s Sci-fi novel Rosewater, from Apex Books, will be released in September 2016.

First, a working definition of SF: fiction that has, at its core, at least one science and/or extrapolation of same to what could be possible.

Second, a (messy) working definition of a science: a field of knowledge that has at its core the scientific method, meaning systematic analyses of observed phenomena including objective observations, hypothesis/null hypothesis, statistical analysis, experimentation, peer review with duplication of findings. I am aware that this definition is a mess.

Defining ‘Hard’ SF is a bit difficult. If we use the Millerian definition (scientific or technical accuracy and detail), it won’t hold water. The reason is not all sciences are equal in SF. In my experience, fictional works that focus on physics, astronomy, mathematics, engineering and (to a lesser extent) chemistry tend to be filed as ‘Hard,’ especially if there is an exploratory or militaristic aspect. The further the extrapolation of the science from what is known, the more likely the story will be classed as ‘soft.’ On the other hand, those that Jeff VanderMeer jokingly refers to as ‘squishy’ sciences like botany, mycology, zoology, etc. tend to be classed as soft SF along with the social sciences like anthropology, psychology, etc. Medicine can fall either way, depending on the actual narrative.

That the definitions are problematic becomes obvious immediately. I find the terms intellectually uninteresting because they assume that social sciences use less rigor, which I know to be untrue. My background is in medicine and anthropology, and I have seen both sides.

There may be other elements to the definitions. There may be a pejorative flavor to being designated ‘soft’. There may be some gender bias, although I have seen this in discussions, and not in print. Take a lot of the work of Ursula Le Guin. Many would not class her SF as ‘Hard’ despite her clear understanding of anthropology and psychology. The exploration of cultures should not take a back seat to the exploration of the solar system. Take Frankenstein, which is often regarded as the first science fiction novel. Few would regard it as Hard SF, yet it used contemporary scientific beliefs. At the time the novel was set, galvanism was a big thing. Reanimation was not thought to be impossible. The Royal Humane Society in England started with reanimation of the dead at its core, and its motto is a small spark may perhaps lie hid.

At the root of the Hard-Soft divide is a kind of “I scienced more than you” attitude, which is unnecessary. There are fans of all flavours of SF and the last thing we need is to focus on divisions that were introduced in the late 1950s.

Elizabeth Bear

Elizabeth Bear’s most recent novel is Karen Memory (Tor 2015). You can find her on Twitter.

I feel like the purported hard/soft SF divide is one of those false dichotomies that humans love so much—like white/black, male/female, and so forth. The thing is, it’s really arbitrary. I write everything from fairy tales to fairly crunchy sciency SF, and I think the habit of shoving all of this stuff into increasingly tiny boxes that really amount to marketing categories is kind of a waste of time. There’s no intrinsic moral element that makes a rigorously extrapolated near-future cascading disaster story (like The Martian) “better” than an equally critically hailed and popular sociological extrapolation. Is anybody going to argue, for example, that 1984 or The Handmaid’s Tale aren’t worthy books because they are about societies in crisis rather than technology?

I love hard—or rigorously extrapolated physical—science fiction, for what it’s worth. My list of favorite books includes Peter Watts, Tricia Sullivan, and Robert L. Forward. But it’s not new, and it’s not dying out. It’s always been a percentage of the field (though Analog still has the biggest readership of any English-language SF magazine, I believe) and it’s still a vibrant presence in our midst, given writers like Kim Stanley Robinson and James L. Cambias, for example. It’s hard to write, and hard to write well, mind, and Andy Weir kind of knocked it out of the park.

My own pocket definition of SF is that it’s the literature of testing concepts to destruction: space travel, societies, ideologies. At its best, that’s what science fiction does that most other literary forms do not. (Most of them—the ones with a literary bent, at least–are about testing people (in the form of people-shaped objects called “characters”) to destruction. Science fiction does it on a scale up to and including entire galaxies, which is kind of cool. Drawing little boxes around one bit of it and saying, “This is the real thing here,” is both basically pointless and basically a kind of classism. It’s the Apollonian/Dionysian divide again, just like the obsession of certain aspects of SF with separating the mind from the meat.

(Spoiler: you can’t: you are your mind, and your mind is a bunch of physical and chemical and electrical processes in some meat. You might be able to SIMULATE some of those processes elsewhere, but it seems to me entirely unlikely that anybody will ever “upload a person,” excepting the unlikely proposition that we somehow find an actual soul somewhere and figure out how to stick it in a soul bottle for later use.)

Anyway, I kind of think it’s a boring and contrived argument, is what I’m saying here.

Max Gladstone

Max Gladstone’s latest novel is Last First Snow (Tor, 2015). Find him on Twitter.

Hard SF is, in theory, SF where the math works. Of course, our knowledge of the universe is limited, so hard SF ends up being “SF where the math works, according to our current understanding of math,” or even “according to the author’s understanding of math,” and often ends up feeling weirdly dated over time. In very early SF you see a lot of “sub-ether” devices, from back when we still thought there might be a luminiferous ether; more recent SF that depends on a “Big Crunch” singularity collapse end of the universe seems very unlikely these days, since observations suggest the universe’s expansion is accelerating. Often you find stories in which the orbital dynamics are exactly right, but everyone’s using computers the size of a house, because of course 33rd century computers will still be made with vacuum tubes, or stories that have decent rocketry but a lousy understanding of genetics, or stories that get both rocketry and genetics right, but don’t have a clue how human societies or beings function.

I don’t think there’s a dichotomy, really. “Hardness” is a graph where the X axis starts at zero, and that’s, say, Star Wars—SF that doesn’t even mention math or orbital dynamics, but is still recognizably SF—and proceeds to, say, Apollo 13, which is so hard it’s not even fiction. On the y axis you have “quality.” You can place every SF text somewhere within that space, but no curve exists. Neal Stephenson’s Cryptonomicon is SF so hard that it borders on a technothriller, but that hardness doesn’t determine its quality when set against, say, The Left Hand of Darkness (where the plot hinges on FTL comms), or Childhood’s End (force fields, psychic storm omega point gestalts, etc.).

But if we really want something to pose against “hard,” how about “sharp SF”? Sharp SF acknowledges that our understanding of the universe is a moving target, and believes the point of SF is to show how human beings, relationships, and societies transform or endure under different conditions. Sharp SF takes math, physics, sociology, economics, political science, anthropology, psychology, etc. into account when posing its hypothetical worlds—but cares more about the human consequences of those hypotheticals than it cares about the hypothetical’s underlying architecture. I’d include 1984, The Handmaid’s Tale, Parable of the Sower, Nova, Dune, and Lord of Light as canonical examples of good sharp SF.

Aliette de Bodard

Aliette de Bodard’s latest novel, The House of Shattered Wings, was published by Roc (US)/Gollancz (RoW) in August 2015.

I think they’re labels, and as labels they’re useful because they tell you what kind of story you’re going to get, and what it’s going to focus on (in the case of hard SF, hard sciences such as maths, physics, computer science, and an emphasis on the nitty-gritty of science and engineering as core to the plot. Soft SF is going to focus more on sociology, societies and the interaction between characters). The issue with labels is twofold: first, they can be used dismissively, i.e., “it’s not real SF if it’s not hard SF,” or “hard SF is the best kind of SF and everything else is of little worth,” which is unfortunately something I see happening all too often. And it’s doubly problematic, because this dismissal is disproportionately used to single out women/POCs/marginalised people as not writing “proper SF.” (I should add that I’ve got nothing whatsoever against hard SF and will quite happily enjoy an Alastair Reynolds or a Hannu Rajaniemi when I’m in the mood for it).

The second issue is that like any labels, they can be restrictive: they can create an impression in the author’s mind that “real SF” should have such and such; and particularly the emphasis on the nitty-gritty of science makes a lot of people feel like they shouldn’t be writing hard SF, that you should have several PhDs and degrees and everyday practice of physics, etc., to even consider writing something. It’s not that it doesn’t help (as someone with a degree in science, I can certainly attest that it helps make things go down more smoothly with only minimal amounts of research), but I worry that it raises a barrier to entry that doesn’t really have a reason to be there. My personal testimony is that I held off from writing SF because I didn’t think I had the chops for it (and that’s in spite of the actual maths/computer science degree…); and also that it took me a long time to write what I actually wanted to write because I was afraid that taking bits and pieces from every subgenre I liked was somehow an unspeakable crime…

Walter Jon Williams

Walter Jon Williams’ novella “Impersonations” will appear from Tor.com Publishing in September 2016.

I’d define Hard SF as a subdivision of Geek Fiction. I’m currently at work on a General Theory of Geek Fiction, and while my ideas are still in flux, I can define Geek Fiction as that fiction in which the greatest emphasis is given to process. The story becomes not one of plot or character or setting—although ideally those are present as well—but a story in which the action is broken down into a series of technical problems to be solved.

Thus The Martian is a book about all the technical problems that need to be surmounted in order to survive on Mars. C.S. Forester’s Hornblower books are about the technical issues involved in commanding square-rigged sailing ships in wartime. Police procedurals are about the process of police procedure. These sorts of books can be about other things as well, but if the emphasis isn’t on process, it’s not Geek Fiction.

As for Soft SF, it’s better to define it by what it is instead of by what it isn’t. After all, Soft SF includes space opera, science fantasy, dystopia, near-future works, alternative history, time travel stories, satirical and comic SF, and great big unclassifiable tours-de-force like Dhalgren. Just call the thing what it is.

Ellen Klages

Ellen Klages (and her co-author Andy Duncan) won the 2014 World Fantasy Award for the novella, “Wakulla Springs,” originally published at Tor.com.

Attempting to differentiate hard and soft science fiction implies that “science” has gradations on some sort of undefined, Mohs-like scale. Talc science vs. diamond science. But that seems to me a misunderstanding of what science is. Science is not an established body of knowledge as much as it is an attempt to explain things that we don’t yet know, and to organize what we do know in a systematic way. It is the manual that the world ought to have come with, but was somehow left out of the box.

Things We Don’t Know is a rather large category to begin with, and is also quite fluid, because everything we do know is continually shifting and changing—our understanding of reality is a work in progress. When most people say “this is hard science fiction” they mean the plot depends on demonstrable, provable, known facts about the physical world. Hard, like concrete, not fluid and mutable like water.

I sometimes think they also mean it in the same sense as when Mac users were looked down on by PC users 30 years ago: if you didn’t know how to program your computer, you didn’t really know how to use one. If it’s not hard (as in difficult to do or to understand), it has less value.

Historically, hard science fiction has been more about how inanimate objects work than how human beings live. More about plot than about character. Go figure. Humans—or at the very least, biological beings—are part of any world, and there’s so, so much we don’t know about them. So studying what makes humans tick—the sciences of sociology, economics, linguistics, psychology, etc.—must surely be as much part of that missing world manual as physics and chemistry. A person is more complex than any machine I can think of, and when we start aggregating into groups and societies and nations, that complexity grows exponentially.

I prefer my science fiction to be well-rounded, exploring and explaining the people as well as the furniture and the landscape.

Maurice Broaddus

Maurice Broaddus’ latest story, “Super Duper Fly” appeared in Apex Magazine.

The thing is, my background is as a hard science guy. I have a B.S. in biology and I can still remember the grumbling during our graduation when those who received degrees in psychology were introduced as fellow graduates of the School of Science. Ironically, even after a 20-year career in environmental toxicology, the science of my SF writing tends to lean to the “soft” side of things.

There is an imagined line in the sand that doesn’t need to be there. In fact, hard and soft SF go hand-in-hand. Much of the SF I’m drawn to turns on the soft science of sociology. The impact of technology in a culture’s development, how people organize, and how people interact with the technology and each other because of it. (Think of how prescient 1984 seems now.) And for all of the hard science of The Martian, it would all be science porn if we also didn’t have the soft science of psychology in play also. A story is ultimately driven by the psychology of its characters.

Linda Nagata

Linda Nagata’s novel The Red: First Light was a Publishers Weekly best book of 2015.

My definition of hard SF is pretty simple and inclusive. It’s science fiction that extrapolates future technologies while trying to adhere to rules of known or plausible science. “Plausible,” of course, being a squishy term and subject to opinion. For me, the science and technology, while interesting in itself, is the background. The story comes from the way that technology affects the lives of the characters.

I don’t use the term “soft science fiction.” It’s one of those words whose meaning is hard to pin down, and likely to change with circumstances. Instead I think about science fiction as a continuum between hard science fiction and space fantasy, with no clear dividing line—although when you’ve wandered well into one or the other, you know it. And besides, just because we’ve split out the hard stuff, that doesn’t mean that everything that’s left can be dumped into the same “not hard” category. So there is science fiction, and within it there is hard science fiction, planetary stories, retro science fiction, space opera, military science fiction, and a lot more—but I don’t have an all-encompassing term for the non-hard stuff.

Michael Swanwick

Michael Swanwick’s latest novel is Chasing the Phoenix (Tor, 2015). He’s won many awards.

I go with what Algis Budrys said, that hard science fiction is not a subgenre but a flavor, and that that flavor is toughness. It doesn’t matter how good your science is, if you don’t understand this you’ll never get street cred for your hard SF story. You not only have to have a problem, but your main character must strive to solve it in the right way—with determination, a touch of stoicism, and the consciousness that the universe is not on his or her side. You can throw in a little speech about the universe wanting to kill your protagonist, if you like, but only Larry Niven has been able to pull that off and make the reader like it.

Source: http://www.tor.com/2016/01/21/how-do-you-like-your-science-fiction-ten-authors-weigh-in-on-hard-vs-soft-sf/

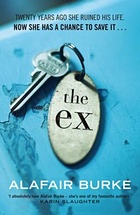

A pleasingly suspenseful mixture of legal thriller and whodunnit, Alafair Burke’s latest novel, The Ex (Faber, £12.99), introduces us to lippy, take-no‑prisoners New York City district attorney Olivia Randall, who receives a panicky phone call from the teenage daughter of her former fiance, Jack Harris, begging for help. Harris, whose wife was killed in a mass shooting three years earlier, has been charged with triple homicide, which the police are treating as a revenge attack because one of the victims is the father of the boy who shot his wife. For Olivia, representing Jack is a way to make up for the hurt she caused him in the past, but his alibi is flimsy and there is corroborating evidence, and she begins to wonder if he may, after all, be guilty. Burke’s writing has always been intelligent and often funny, and her female protagonists sharp and engaging – The Ex is her best yet.

A pleasingly suspenseful mixture of legal thriller and whodunnit, Alafair Burke’s latest novel, The Ex (Faber, £12.99), introduces us to lippy, take-no‑prisoners New York City district attorney Olivia Randall, who receives a panicky phone call from the teenage daughter of her former fiance, Jack Harris, begging for help. Harris, whose wife was killed in a mass shooting three years earlier, has been charged with triple homicide, which the police are treating as a revenge attack because one of the victims is the father of the boy who shot his wife. For Olivia, representing Jack is a way to make up for the hurt she caused him in the past, but his alibi is flimsy and there is corroborating evidence, and she begins to wonder if he may, after all, be guilty. Burke’s writing has always been intelligent and often funny, and her female protagonists sharp and engaging – The Ex is her best yet.

Seeing old books with renewed eyes

Huckleberry Finn, Alive at 100

By NORMAN MAILER

Published: December 9, 1984

Source: http://www.nytimes.com/1984/12/09/books/mailer-huck.html?smid=fb-share&pagewanted=all

[Editor’s note: This essay of rediscovering a classic in adulthood was written over 30 years ago, but is still true today.]

Is there a sweeter tonic for the doldrums than old reviews of great novels? In 19th-century Russia, ”Anna Karenina” was received with the following: ”Vronsky’s passion for his horse runs parallel to his passion for Anna” . . . ”Sentimental rubbish” . . . ”Show me one page,” says The Odessa Courier, ”that contains an idea.” ”Moby-Dick” was incinerated: ”Graphic descriptions of a dreariness such as we do not remember to have met with before in marine literature” . . . ”Sheer moonstruck lunacy” . . . ”Sad stuff. Mr. Melville’s Quakers are wretched dolts and drivellers and his mad captain is a monstrous bore.”

Annotated edition of “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn”

All the same, the novel was not too unpleasantly regarded. There were no large critical hurrahs but the reviews were, on the whole, friendly. A good tale, went the consensus. There was no sense that a great American novel had landed on the literary world of 1885. The critical climate could hardly anticipate T. S. Eliot and Ernest Hemingway’s encomiums 50 years later. In the preface to an English edition, Eliot would speak of ”a master piece. . . . Twain’s genius is completely realized,” and Ernest went further. In ”Green Hills of Africa,” after disposing of Emerson, Hawthorne and Thoreau, and paying off Henry James and Stephen Crane with a friendly nod, he proceeded to declare, ”All modern American literture comes from one book by Mark Twain called ‘Huckleberry Finn.’ . . . It’s the best book we’ve had. All American writing comes from that. There was nothing before. There has been nothing as good since.”

Hemingway, with his nonpareil gift for nosing out the perfect vin du pays for an ineluctable afternoon, was nonetheless more like other novelists in one dire respect: he was never at a loss to advance himself with his literary judgments. Assessing the writing of others, he used the working author’s rule of thumb: if I give this book a good mark, does it help appreciation of my work? Obviously, ”Huckleberry Finn” has passed the test.

A SUSPICION immediately arises. Mark Twain is doing the kind of writing only Hemingway can do better. Evidently, we must take a look. May I say it helps to have read ”Huckleberry Finn” so long ago that it feels brand-new on picking it up again. Perhaps I was 11 when I saw it last, maybe 13, but now I only remember that I came to it after ”Tom Sawyer” and was disappointed. I couldn’t really follow ”The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.” The character of Tom Sawyer whom I had liked so much in the first book was altered, and did not seem nice any more. Huckleberry Finn was altogether beyond me. Later, I recollect being surprised by the high regard nearly everyone who taught American Lit. lavished upon the text, but that didn’t bring me back to it. Obviously, I was waiting for an assignment from The New York Times.

Let me offer assurances. It may have been worth the wait. I suppose I am the 10-millionth reader to say that ”Huckleberry Finn” is an extraordinary work. Indeed, for all I know, it is a great novel. Flawed, quirky, uneven, not above taking cheap shots and cashing far too many checks (it is rarely above milking its humor) – all the same, what a book we have here! I had the most curious sense of excitement. After a while, I understood my peculiar frame of attention. The book was so up-to- date! I was not reading a classic author so much as looking at a new work sent to me in galleys by a publisher. It was as if it had arrived with one of those rare letters which says, ”We won’t make this claim often but do think we have an extraordinary first novel to send out.” So it was like reading ”From Here to Eternity” in galleys, back in 1950, or ”Lie Down in Darkness,” ”Catch-22,” or ”The World According to Garp” (which reads like a fabulous first novel). You kept being alternately delighted, surprised, annoyed, competitive, critical and finally excited. A new writer had moved onto the block. He could be a potential friend or enemy but he most certainly was talented.

That was how it felt to read ”Huckleberry Finn” a second time. I kept resisting the context until I finally surrendered. One always does surrender sooner or later to a book with a strong magnetic field. I felt as if I held the work of a young writer about 30 or 35, a prodigiously talented fellow from the Midwest, from Missouri probably, who had had the audacity to write a historical novel about the Mississippi as it might have been a century and a half ago, and this young writer had managed to give us a circus of fictional virtuosities. In nearly every chapter new and remarkable characters bounded out from the printed page as if it were a tarmac on which they could perform their leaps. The author’s confidence seemed so complete that he could deal with every kind of man or woman God ever gave to the middle of America. Jail-house drunks like Huck Finn’s father take their bow, full of the raunchy violence that even gets into the smell of clothing. Gentlemen and river rats, young, attractive girls full of grit and ”sand,” and strong old ladies with aphorisms clicking like knitting needles, fools and confidence men – what a cornucopia of rabble and gentry inhabit the author’s river banks.

It would be superb stuff if only the writer did not keep giving away the fact that he was a modern young American working in 1984. His anachronisms were not so much in the historical facts – those seemed accurate enough – but the point of view was too contemporary. The scenes might succeed – say it again, this young writer was talented! – but he kept betraying his literary influences. The author of ”The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” had obviously been taught a lot by such major writers as Sinclair Lewis, John Dos Passos and John Steinbeck; he had certainly lifted from Faulkner and the mad tone Faulkner could achieve when writing about maniacal men feuding in deep swamps; he had also absorbed much of what Vonnegut and Heller could teach about the resilience of irony. If he had a surer feel for the picaresque than Saul Bellow in ”Augie March,” still he felt derivative of that work. In places one could swear he had memorized ”The Catcher in the Rye,” and he probably dipped into ”Deliverance” and ”Why Are We in Vietnam?” He might even have studied the mannerisms of movie stars. You could feel traces of John Wayne, Victor McLaglen and Burt Reynolds in his pages. The author had doubtless digested many a Hollywood comedy on small-town life. His instinct for life in hamlets on the Mississippi before the Civil War was as sharp as it was farcical, and couldn’t be more commercial.

No matter. With talent as large as this, one could forgive the obvious eye for success. Many a large talent has to go through large borrowings in order to find his own style, and a lust for popular success while dangerous to serious writing is not necessarily fatal. Yes, one could accept the pilferings from other writers, given the scope of this work, the brilliance of the concept – to catch rural America by a trip on a raft down a great river! One could even marvel uneasily at the depth of the instinct for fiction in the author. With the boy Huckleberry Finn, this new novelist had managed to give us a character of no comfortable, measurable dimension. It is easy for characters in modern novels to seem more vivid than figures in the classics but, even so, Huckleberry Finn appeared to be more alive than Don Quixote and Julian Sorel, as naturally near to his own mind as we are to ours. But how often does a hero who is so absolutely natural on the page also succeed in acquiring convincing moral stature as his adventures develop?

It is to be repeated. In the attractive grip of this talent, one is ready to forgive the author of ”Huckleberry Finn” for every influence he has so promiscuously absorbed. He has made such fertile use of his borrowings. One could even cheer his appearance on our jaded literary scene if not for the single transgression that goes too far. These are passages that do more than borrow an author’s style – they copy it! Influence is mental, but theft is physical. Who can declare to a certainty that a large part of the prose in ”Huckleberry Finn” is not lifted directly from Hemingway? We know that we are not reading Ernest only because the author, obviously fearful that his tone is getting too near, is careful to sprinkle his text with ”a-clutterings” and ”warn’ts” and ”anywheres” and ”t’others.” But we have read Hemingway – and so we see through it – we know we are reading pure Hemingway disguised:

”We cut young cottonwoods and willows, and hid the raft with them. Then we set out the lines. Next we slid into the river and had a swim . . . then we set down on the sandy bottom where the water was about knee-deep and watched the daylight come. Not a sound anywheres . . . the first thing to see, looking away over the water, was a kind of dull line – that was the woods on t’other side; you couldn’t make nothing else out; then a pale place in the sky; then more paleness spreading around; then the river softened up away off, and warn’t black anymore . . . by and by you could see a streak on the water which you know by the look of the streak that there’s a snag there in a swift current which breaks on it and makes that streak look that way; and you see the mist curl up off of the water and the east reddens up and the river.”

Up to now I have conveyed, I expect, the pleasure of reading this book today. It is the finest compliment I can offer. We use an unspoken standard of relative judgment on picking up a classic. Secretly, we expect less reward from it than from a good contemporary novel. The average intelligent modern reader would probably, under torture, admit that ”Heartburn” was more fun to read, minute for minute, than ”Madame Bovary,” and maybe one even learned more. That is not to say that the first will be superior to the second a hundred years from now but that a classic novel is like a fine horse carrying an exorbitant impost. Classics suffer by their distance from our day-to-day gossip. The mark of how good ”Huckleberry Finn” has to be is that one can compare it to a number of our best modern American novels and it stands up page for page, awkward here, sensational there – absolutely the equal of one of those rare incredible first novels that come along once or twice in a decade. So I have spoken of it as kin to a first novel because it is so young and so fresh and so all-out silly in some of the chances it takes and even wins. A wiser older novelist would never play that far out when the work was already well along and so neatly in hand. But Twain does.

For the sake of literary propriety, let me not, however, lose sight of the actual context. ”The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” is a novel of the 19th century and its grand claims to literary magnitude are also to be remarked upon. So I will say that the first measure of a great novel may be that it presents – like a human of palpable charisma – an all-but-visible aura. Few works of literature can be so luminous without the presence of some majestic symbol. In ”Huckleberry Finn” we are presented (given the possible exception of Anna Livia Plurabelle) with the best river ever to flow through a novel, our own Mississippi, and in the voyage down those waters of Huck Finn and a runaway slave on their raft, we are held in the thrall of the river. Larger than a character, the river is a manifest presence, a demiurge to support the man and the boy, a deity to betray them, feed them, all but drown them, fling them apart, float them back together. The river winds like a fugue through the marrow of the true narrative which is nothing less than the ongoing relation between Huck and the runaway slave, this Nigger Jim whose name embodies the very stuff of the slave system itself – his name is not Jim but Nigger Jim. The growth of love and knowledge between the runaway white and the runaway black is a relation equal to the relation of the men to the river for it is also full of betrayal and nourishment, separation and return. So it manages to touch that last fine nerve of the heart where compassion and irony speak to one another and thereby give a good turn to our most protected emotions.

READING ”Huckleberry Finn” one comes to realize all over again that the near- burned-out, throttled, hate-filled dying affair between whites and blacks is still our great national love affair, and woe to us if it ends in detestation and mutual misery. Riding the current of this novel, we are back in that happy time when the love affair was new and all seemed possible. How rich is the recollection of that emotion! What else is greatness but the indestructible wealth it leaves in the mind’s recollection after hope has soured and passions are spent? It is always the hope of democracy that our wealth will be there to spend again, and the ongoing treasure of ”Huckleberry Finn” is that it frees us to think of democracy and its sublime, terrifying premise: let the passions and cupidities and dreams and kinks and ideals and greed and hopes and foul corruptions of all men and women have their day and the world will still be better off, for there is more good than bad in the sum of us and our workings. Mark Twain, whole embodiment of that democratic human, understood the premise in every turn of his pen, and how he tested it, how he twisted and tantalized and tested it until we are weak all over again with our love for the idea.

Norman Mailer’s latest novel is ”Tough Guys Don’t Dance.”

Source: http://www.nytimes.com/1984/12/09/books/mailer-huck.html?smid=fb-share&pagewanted=all

Share this:

Leave a comment

Filed under 2016, author commentary, authors

Tagged as Huckleberry Finn, Mark Twain, Norman Mailer, Saturday