Huckleberry Finn, Alive at 100

By NORMAN MAILER

Published: December 9, 1984

Source: http://www.nytimes.com/1984/12/09/books/mailer-huck.html?smid=fb-share&pagewanted=all

[Editor’s note: This essay of rediscovering a classic in adulthood was written over 30 years ago, but is still true today.]

Is there a sweeter tonic for the doldrums than old reviews of great novels? In 19th-century Russia, ”Anna Karenina” was received with the following: ”Vronsky’s passion for his horse runs parallel to his passion for Anna” . . . ”Sentimental rubbish” . . . ”Show me one page,” says The Odessa Courier, ”that contains an idea.” ”Moby-Dick” was incinerated: ”Graphic descriptions of a dreariness such as we do not remember to have met with before in marine literature” . . . ”Sheer moonstruck lunacy” . . . ”Sad stuff. Mr. Melville’s Quakers are wretched dolts and drivellers and his mad captain is a monstrous bore.”

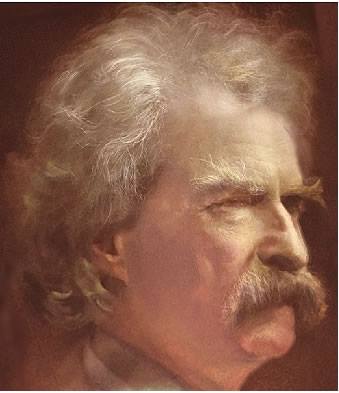

Annotated edition of “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn”

By this measure, ”Huckleberry Finn” (published 100 years ago this week in London and two months later in America) gets off lightly. The Springfield Republican judged it to be no worse than ”a gross trifling with every fine feeling. . . . Mr. Clemens has no reliable sense of propriety,” and the public library in Concord, Mass., was confident enough to ban it: ”the veriest trash.” The Boston Transcript reported that ”other members of the Library Committee characterize the work as rough, coarse, and inelegant, the whole book being more suited to the slums than to intelligent, respectable people.”

All the same, the novel was not too unpleasantly regarded. There were no large critical hurrahs but the reviews were, on the whole, friendly. A good tale, went the consensus. There was no sense that a great American novel had landed on the literary world of 1885. The critical climate could hardly anticipate T. S. Eliot and Ernest Hemingway’s encomiums 50 years later. In the preface to an English edition, Eliot would speak of ”a master piece. . . . Twain’s genius is completely realized,” and Ernest went further. In ”Green Hills of Africa,” after disposing of Emerson, Hawthorne and Thoreau, and paying off Henry James and Stephen Crane with a friendly nod, he proceeded to declare, ”All modern American literture comes from one book by Mark Twain called ‘Huckleberry Finn.’ . . . It’s the best book we’ve had. All American writing comes from that. There was nothing before. There has been nothing as good since.”

Hemingway, with his nonpareil gift for nosing out the perfect vin du pays for an ineluctable afternoon, was nonetheless more like other novelists in one dire respect: he was never at a loss to advance himself with his literary judgments. Assessing the writing of others, he used the working author’s rule of thumb: if I give this book a good mark, does it help appreciation of my work? Obviously, ”Huckleberry Finn” has passed the test.

A SUSPICION immediately arises. Mark Twain is doing the kind of writing only Hemingway can do better. Evidently, we must take a look. May I say it helps to have read ”Huckleberry Finn” so long ago that it feels brand-new on picking it up again. Perhaps I was 11 when I saw it last, maybe 13, but now I only remember that I came to it after ”Tom Sawyer” and was disappointed. I couldn’t really follow ”The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.” The character of Tom Sawyer whom I had liked so much in the first book was altered, and did not seem nice any more. Huckleberry Finn was altogether beyond me. Later, I recollect being surprised by the high regard nearly everyone who taught American Lit. lavished upon the text, but that didn’t bring me back to it. Obviously, I was waiting for an assignment from The New York Times.

Let me offer assurances. It may have been worth the wait. I suppose I am the 10-millionth reader to say that ”Huckleberry Finn” is an extraordinary work. Indeed, for all I know, it is a great novel. Flawed, quirky, uneven, not above taking cheap shots and cashing far too many checks (it is rarely above milking its humor) – all the same, what a book we have here! I had the most curious sense of excitement. After a while, I understood my peculiar frame of attention. The book was so up-to- date! I was not reading a classic author so much as looking at a new work sent to me in galleys by a publisher. It was as if it had arrived with one of those rare letters which says, ”We won’t make this claim often but do think we have an extraordinary first novel to send out.” So it was like reading ”From Here to Eternity” in galleys, back in 1950, or ”Lie Down in Darkness,” ”Catch-22,” or ”The World According to Garp” (which reads like a fabulous first novel). You kept being alternately delighted, surprised, annoyed, competitive, critical and finally excited. A new writer had moved onto the block. He could be a potential friend or enemy but he most certainly was talented.

That was how it felt to read ”Huckleberry Finn” a second time. I kept resisting the context until I finally surrendered. One always does surrender sooner or later to a book with a strong magnetic field. I felt as if I held the work of a young writer about 30 or 35, a prodigiously talented fellow from the Midwest, from Missouri probably, who had had the audacity to write a historical novel about the Mississippi as it might have been a century and a half ago, and this young writer had managed to give us a circus of fictional virtuosities. In nearly every chapter new and remarkable characters bounded out from the printed page as if it were a tarmac on which they could perform their leaps. The author’s confidence seemed so complete that he could deal with every kind of man or woman God ever gave to the middle of America. Jail-house drunks like Huck Finn’s father take their bow, full of the raunchy violence that even gets into the smell of clothing. Gentlemen and river rats, young, attractive girls full of grit and ”sand,” and strong old ladies with aphorisms clicking like knitting needles, fools and confidence men – what a cornucopia of rabble and gentry inhabit the author’s river banks.

It would be superb stuff if only the writer did not keep giving away the fact that he was a modern young American working in 1984. His anachronisms were not so much in the historical facts – those seemed accurate enough – but the point of view was too contemporary. The scenes might succeed – say it again, this young writer was talented! – but he kept betraying his literary influences. The author of ”The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” had obviously been taught a lot by such major writers as Sinclair Lewis, John Dos Passos and John Steinbeck; he had certainly lifted from Faulkner and the mad tone Faulkner could achieve when writing about maniacal men feuding in deep swamps; he had also absorbed much of what Vonnegut and Heller could teach about the resilience of irony. If he had a surer feel for the picaresque than Saul Bellow in ”Augie March,” still he felt derivative of that work. In places one could swear he had memorized ”The Catcher in the Rye,” and he probably dipped into ”Deliverance” and ”Why Are We in Vietnam?” He might even have studied the mannerisms of movie stars. You could feel traces of John Wayne, Victor McLaglen and Burt Reynolds in his pages. The author had doubtless digested many a Hollywood comedy on small-town life. His instinct for life in hamlets on the Mississippi before the Civil War was as sharp as it was farcical, and couldn’t be more commercial.

No matter. With talent as large as this, one could forgive the obvious eye for success. Many a large talent has to go through large borrowings in order to find his own style, and a lust for popular success while dangerous to serious writing is not necessarily fatal. Yes, one could accept the pilferings from other writers, given the scope of this work, the brilliance of the concept – to catch rural America by a trip on a raft down a great river! One could even marvel uneasily at the depth of the instinct for fiction in the author. With the boy Huckleberry Finn, this new novelist had managed to give us a character of no comfortable, measurable dimension. It is easy for characters in modern novels to seem more vivid than figures in the classics but, even so, Huckleberry Finn appeared to be more alive than Don Quixote and Julian Sorel, as naturally near to his own mind as we are to ours. But how often does a hero who is so absolutely natural on the page also succeed in acquiring convincing moral stature as his adventures develop?

It is to be repeated. In the attractive grip of this talent, one is ready to forgive the author of ”Huckleberry Finn” for every influence he has so promiscuously absorbed. He has made such fertile use of his borrowings. One could even cheer his appearance on our jaded literary scene if not for the single transgression that goes too far. These are passages that do more than borrow an author’s style – they copy it! Influence is mental, but theft is physical. Who can declare to a certainty that a large part of the prose in ”Huckleberry Finn” is not lifted directly from Hemingway? We know that we are not reading Ernest only because the author, obviously fearful that his tone is getting too near, is careful to sprinkle his text with ”a-clutterings” and ”warn’ts” and ”anywheres” and ”t’others.” But we have read Hemingway – and so we see through it – we know we are reading pure Hemingway disguised:

”We cut young cottonwoods and willows, and hid the raft with them. Then we set out the lines. Next we slid into the river and had a swim . . . then we set down on the sandy bottom where the water was about knee-deep and watched the daylight come. Not a sound anywheres . . . the first thing to see, looking away over the water, was a kind of dull line – that was the woods on t’other side; you couldn’t make nothing else out; then a pale place in the sky; then more paleness spreading around; then the river softened up away off, and warn’t black anymore . . . by and by you could see a streak on the water which you know by the look of the streak that there’s a snag there in a swift current which breaks on it and makes that streak look that way; and you see the mist curl up off of the water and the east reddens up and the river.”

Up to now I have conveyed, I expect, the pleasure of reading this book today. It is the finest compliment I can offer. We use an unspoken standard of relative judgment on picking up a classic. Secretly, we expect less reward from it than from a good contemporary novel. The average intelligent modern reader would probably, under torture, admit that ”Heartburn” was more fun to read, minute for minute, than ”Madame Bovary,” and maybe one even learned more. That is not to say that the first will be superior to the second a hundred years from now but that a classic novel is like a fine horse carrying an exorbitant impost. Classics suffer by their distance from our day-to-day gossip. The mark of how good ”Huckleberry Finn” has to be is that one can compare it to a number of our best modern American novels and it stands up page for page, awkward here, sensational there – absolutely the equal of one of those rare incredible first novels that come along once or twice in a decade. So I have spoken of it as kin to a first novel because it is so young and so fresh and so all-out silly in some of the chances it takes and even wins. A wiser older novelist would never play that far out when the work was already well along and so neatly in hand. But Twain does.

For the sake of literary propriety, let me not, however, lose sight of the actual context. ”The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” is a novel of the 19th century and its grand claims to literary magnitude are also to be remarked upon. So I will say that the first measure of a great novel may be that it presents – like a human of palpable charisma – an all-but-visible aura. Few works of literature can be so luminous without the presence of some majestic symbol. In ”Huckleberry Finn” we are presented (given the possible exception of Anna Livia Plurabelle) with the best river ever to flow through a novel, our own Mississippi, and in the voyage down those waters of Huck Finn and a runaway slave on their raft, we are held in the thrall of the river. Larger than a character, the river is a manifest presence, a demiurge to support the man and the boy, a deity to betray them, feed them, all but drown them, fling them apart, float them back together. The river winds like a fugue through the marrow of the true narrative which is nothing less than the ongoing relation between Huck and the runaway slave, this Nigger Jim whose name embodies the very stuff of the slave system itself – his name is not Jim but Nigger Jim. The growth of love and knowledge between the runaway white and the runaway black is a relation equal to the relation of the men to the river for it is also full of betrayal and nourishment, separation and return. So it manages to touch that last fine nerve of the heart where compassion and irony speak to one another and thereby give a good turn to our most protected emotions.

READING ”Huckleberry Finn” one comes to realize all over again that the near- burned-out, throttled, hate-filled dying affair between whites and blacks is still our great national love affair, and woe to us if it ends in detestation and mutual misery. Riding the current of this novel, we are back in that happy time when the love affair was new and all seemed possible. How rich is the recollection of that emotion! What else is greatness but the indestructible wealth it leaves in the mind’s recollection after hope has soured and passions are spent? It is always the hope of democracy that our wealth will be there to spend again, and the ongoing treasure of ”Huckleberry Finn” is that it frees us to think of democracy and its sublime, terrifying premise: let the passions and cupidities and dreams and kinks and ideals and greed and hopes and foul corruptions of all men and women have their day and the world will still be better off, for there is more good than bad in the sum of us and our workings. Mark Twain, whole embodiment of that democratic human, understood the premise in every turn of his pen, and how he tested it, how he twisted and tantalized and tested it until we are weak all over again with our love for the idea.

Norman Mailer’s latest novel is ”Tough Guys Don’t Dance.”

Source: http://www.nytimes.com/1984/12/09/books/mailer-huck.html?smid=fb-share&pagewanted=all

Seeing old books with renewed eyes

Huckleberry Finn, Alive at 100

By NORMAN MAILER

Published: December 9, 1984

Source: http://www.nytimes.com/1984/12/09/books/mailer-huck.html?smid=fb-share&pagewanted=all

[Editor’s note: This essay of rediscovering a classic in adulthood was written over 30 years ago, but is still true today.]

Is there a sweeter tonic for the doldrums than old reviews of great novels? In 19th-century Russia, ”Anna Karenina” was received with the following: ”Vronsky’s passion for his horse runs parallel to his passion for Anna” . . . ”Sentimental rubbish” . . . ”Show me one page,” says The Odessa Courier, ”that contains an idea.” ”Moby-Dick” was incinerated: ”Graphic descriptions of a dreariness such as we do not remember to have met with before in marine literature” . . . ”Sheer moonstruck lunacy” . . . ”Sad stuff. Mr. Melville’s Quakers are wretched dolts and drivellers and his mad captain is a monstrous bore.”

Annotated edition of “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn”

All the same, the novel was not too unpleasantly regarded. There were no large critical hurrahs but the reviews were, on the whole, friendly. A good tale, went the consensus. There was no sense that a great American novel had landed on the literary world of 1885. The critical climate could hardly anticipate T. S. Eliot and Ernest Hemingway’s encomiums 50 years later. In the preface to an English edition, Eliot would speak of ”a master piece. . . . Twain’s genius is completely realized,” and Ernest went further. In ”Green Hills of Africa,” after disposing of Emerson, Hawthorne and Thoreau, and paying off Henry James and Stephen Crane with a friendly nod, he proceeded to declare, ”All modern American literture comes from one book by Mark Twain called ‘Huckleberry Finn.’ . . . It’s the best book we’ve had. All American writing comes from that. There was nothing before. There has been nothing as good since.”

Hemingway, with his nonpareil gift for nosing out the perfect vin du pays for an ineluctable afternoon, was nonetheless more like other novelists in one dire respect: he was never at a loss to advance himself with his literary judgments. Assessing the writing of others, he used the working author’s rule of thumb: if I give this book a good mark, does it help appreciation of my work? Obviously, ”Huckleberry Finn” has passed the test.

A SUSPICION immediately arises. Mark Twain is doing the kind of writing only Hemingway can do better. Evidently, we must take a look. May I say it helps to have read ”Huckleberry Finn” so long ago that it feels brand-new on picking it up again. Perhaps I was 11 when I saw it last, maybe 13, but now I only remember that I came to it after ”Tom Sawyer” and was disappointed. I couldn’t really follow ”The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.” The character of Tom Sawyer whom I had liked so much in the first book was altered, and did not seem nice any more. Huckleberry Finn was altogether beyond me. Later, I recollect being surprised by the high regard nearly everyone who taught American Lit. lavished upon the text, but that didn’t bring me back to it. Obviously, I was waiting for an assignment from The New York Times.

Let me offer assurances. It may have been worth the wait. I suppose I am the 10-millionth reader to say that ”Huckleberry Finn” is an extraordinary work. Indeed, for all I know, it is a great novel. Flawed, quirky, uneven, not above taking cheap shots and cashing far too many checks (it is rarely above milking its humor) – all the same, what a book we have here! I had the most curious sense of excitement. After a while, I understood my peculiar frame of attention. The book was so up-to- date! I was not reading a classic author so much as looking at a new work sent to me in galleys by a publisher. It was as if it had arrived with one of those rare letters which says, ”We won’t make this claim often but do think we have an extraordinary first novel to send out.” So it was like reading ”From Here to Eternity” in galleys, back in 1950, or ”Lie Down in Darkness,” ”Catch-22,” or ”The World According to Garp” (which reads like a fabulous first novel). You kept being alternately delighted, surprised, annoyed, competitive, critical and finally excited. A new writer had moved onto the block. He could be a potential friend or enemy but he most certainly was talented.

That was how it felt to read ”Huckleberry Finn” a second time. I kept resisting the context until I finally surrendered. One always does surrender sooner or later to a book with a strong magnetic field. I felt as if I held the work of a young writer about 30 or 35, a prodigiously talented fellow from the Midwest, from Missouri probably, who had had the audacity to write a historical novel about the Mississippi as it might have been a century and a half ago, and this young writer had managed to give us a circus of fictional virtuosities. In nearly every chapter new and remarkable characters bounded out from the printed page as if it were a tarmac on which they could perform their leaps. The author’s confidence seemed so complete that he could deal with every kind of man or woman God ever gave to the middle of America. Jail-house drunks like Huck Finn’s father take their bow, full of the raunchy violence that even gets into the smell of clothing. Gentlemen and river rats, young, attractive girls full of grit and ”sand,” and strong old ladies with aphorisms clicking like knitting needles, fools and confidence men – what a cornucopia of rabble and gentry inhabit the author’s river banks.

It would be superb stuff if only the writer did not keep giving away the fact that he was a modern young American working in 1984. His anachronisms were not so much in the historical facts – those seemed accurate enough – but the point of view was too contemporary. The scenes might succeed – say it again, this young writer was talented! – but he kept betraying his literary influences. The author of ”The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” had obviously been taught a lot by such major writers as Sinclair Lewis, John Dos Passos and John Steinbeck; he had certainly lifted from Faulkner and the mad tone Faulkner could achieve when writing about maniacal men feuding in deep swamps; he had also absorbed much of what Vonnegut and Heller could teach about the resilience of irony. If he had a surer feel for the picaresque than Saul Bellow in ”Augie March,” still he felt derivative of that work. In places one could swear he had memorized ”The Catcher in the Rye,” and he probably dipped into ”Deliverance” and ”Why Are We in Vietnam?” He might even have studied the mannerisms of movie stars. You could feel traces of John Wayne, Victor McLaglen and Burt Reynolds in his pages. The author had doubtless digested many a Hollywood comedy on small-town life. His instinct for life in hamlets on the Mississippi before the Civil War was as sharp as it was farcical, and couldn’t be more commercial.

No matter. With talent as large as this, one could forgive the obvious eye for success. Many a large talent has to go through large borrowings in order to find his own style, and a lust for popular success while dangerous to serious writing is not necessarily fatal. Yes, one could accept the pilferings from other writers, given the scope of this work, the brilliance of the concept – to catch rural America by a trip on a raft down a great river! One could even marvel uneasily at the depth of the instinct for fiction in the author. With the boy Huckleberry Finn, this new novelist had managed to give us a character of no comfortable, measurable dimension. It is easy for characters in modern novels to seem more vivid than figures in the classics but, even so, Huckleberry Finn appeared to be more alive than Don Quixote and Julian Sorel, as naturally near to his own mind as we are to ours. But how often does a hero who is so absolutely natural on the page also succeed in acquiring convincing moral stature as his adventures develop?

It is to be repeated. In the attractive grip of this talent, one is ready to forgive the author of ”Huckleberry Finn” for every influence he has so promiscuously absorbed. He has made such fertile use of his borrowings. One could even cheer his appearance on our jaded literary scene if not for the single transgression that goes too far. These are passages that do more than borrow an author’s style – they copy it! Influence is mental, but theft is physical. Who can declare to a certainty that a large part of the prose in ”Huckleberry Finn” is not lifted directly from Hemingway? We know that we are not reading Ernest only because the author, obviously fearful that his tone is getting too near, is careful to sprinkle his text with ”a-clutterings” and ”warn’ts” and ”anywheres” and ”t’others.” But we have read Hemingway – and so we see through it – we know we are reading pure Hemingway disguised:

”We cut young cottonwoods and willows, and hid the raft with them. Then we set out the lines. Next we slid into the river and had a swim . . . then we set down on the sandy bottom where the water was about knee-deep and watched the daylight come. Not a sound anywheres . . . the first thing to see, looking away over the water, was a kind of dull line – that was the woods on t’other side; you couldn’t make nothing else out; then a pale place in the sky; then more paleness spreading around; then the river softened up away off, and warn’t black anymore . . . by and by you could see a streak on the water which you know by the look of the streak that there’s a snag there in a swift current which breaks on it and makes that streak look that way; and you see the mist curl up off of the water and the east reddens up and the river.”

Up to now I have conveyed, I expect, the pleasure of reading this book today. It is the finest compliment I can offer. We use an unspoken standard of relative judgment on picking up a classic. Secretly, we expect less reward from it than from a good contemporary novel. The average intelligent modern reader would probably, under torture, admit that ”Heartburn” was more fun to read, minute for minute, than ”Madame Bovary,” and maybe one even learned more. That is not to say that the first will be superior to the second a hundred years from now but that a classic novel is like a fine horse carrying an exorbitant impost. Classics suffer by their distance from our day-to-day gossip. The mark of how good ”Huckleberry Finn” has to be is that one can compare it to a number of our best modern American novels and it stands up page for page, awkward here, sensational there – absolutely the equal of one of those rare incredible first novels that come along once or twice in a decade. So I have spoken of it as kin to a first novel because it is so young and so fresh and so all-out silly in some of the chances it takes and even wins. A wiser older novelist would never play that far out when the work was already well along and so neatly in hand. But Twain does.

For the sake of literary propriety, let me not, however, lose sight of the actual context. ”The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” is a novel of the 19th century and its grand claims to literary magnitude are also to be remarked upon. So I will say that the first measure of a great novel may be that it presents – like a human of palpable charisma – an all-but-visible aura. Few works of literature can be so luminous without the presence of some majestic symbol. In ”Huckleberry Finn” we are presented (given the possible exception of Anna Livia Plurabelle) with the best river ever to flow through a novel, our own Mississippi, and in the voyage down those waters of Huck Finn and a runaway slave on their raft, we are held in the thrall of the river. Larger than a character, the river is a manifest presence, a demiurge to support the man and the boy, a deity to betray them, feed them, all but drown them, fling them apart, float them back together. The river winds like a fugue through the marrow of the true narrative which is nothing less than the ongoing relation between Huck and the runaway slave, this Nigger Jim whose name embodies the very stuff of the slave system itself – his name is not Jim but Nigger Jim. The growth of love and knowledge between the runaway white and the runaway black is a relation equal to the relation of the men to the river for it is also full of betrayal and nourishment, separation and return. So it manages to touch that last fine nerve of the heart where compassion and irony speak to one another and thereby give a good turn to our most protected emotions.

READING ”Huckleberry Finn” one comes to realize all over again that the near- burned-out, throttled, hate-filled dying affair between whites and blacks is still our great national love affair, and woe to us if it ends in detestation and mutual misery. Riding the current of this novel, we are back in that happy time when the love affair was new and all seemed possible. How rich is the recollection of that emotion! What else is greatness but the indestructible wealth it leaves in the mind’s recollection after hope has soured and passions are spent? It is always the hope of democracy that our wealth will be there to spend again, and the ongoing treasure of ”Huckleberry Finn” is that it frees us to think of democracy and its sublime, terrifying premise: let the passions and cupidities and dreams and kinks and ideals and greed and hopes and foul corruptions of all men and women have their day and the world will still be better off, for there is more good than bad in the sum of us and our workings. Mark Twain, whole embodiment of that democratic human, understood the premise in every turn of his pen, and how he tested it, how he twisted and tantalized and tested it until we are weak all over again with our love for the idea.

Norman Mailer’s latest novel is ”Tough Guys Don’t Dance.”

Source: http://www.nytimes.com/1984/12/09/books/mailer-huck.html?smid=fb-share&pagewanted=all

Share this:

Leave a comment

Filed under 2016, author commentary, authors

Tagged as Huckleberry Finn, Mark Twain, Norman Mailer, Saturday