Such vulgar venality voices voluminous volumes verifying very vituperative vociferous vilification vouchsafing the vagabond verity of English’s vocabulary. Verily, I say.

Such vulgar venality voices voluminous volumes verifying very vituperative vociferous vilification vouchsafing the vagabond verity of English’s vocabulary. Verily, I say.

Filed under 2023, humor, word play, words, Words to live by

By Hélène Schumacher, 26th June 2020

‘The’. It’s omnipresent; we can’t imagine English without it. But it’s not much to look at. It isn’t descriptive, evocative or inspiring. Technically, it’s meaningless. And yet this bland and innocuous-seeming word could be one of the most potent in the English language.

This story was originally published in January 2020.

More like this:

– The surprising history of the word ‘dude’

– The story of handwriting in 12 objects

– What a single sound says about you

‘The’ tops the league tables of most frequently used words in English, accounting for 5% of every 100 words used. “‘The’ really is miles above everything else,” says Jonathan Culpeper, professor of linguistics at Lancaster University. But why is this? The answer is two-fold, according to the BBC Radio 4 programme Word of Mouth. George Zipf, a 20th-Century US linguist and philologist, expounded the principle of least effort. He predicted that short and simple words would be the most frequent – and he was right.

The second reason is that ‘the’ lies at the heart of English grammar, having a function rather than a meaning. Words are split into two categories: expressions with a semantic meaning and functional words like ‘the’, ‘to’, ‘for’, with a job to do. ‘The’ can function in multiple ways. This is typical, explains Gary Thoms, assistant professor in linguistics at New York University: “a super high-usage word will often develop a real flexibility”, with different subtle uses that make it hard to define. Helping us understand what is being referred to, ‘the’ makes sense of nouns as a subject or an object. So even someone with a rudimentary grasp of English can tell the difference between ‘I ate an apple’ and ‘I ate the apple’.

But although ‘the’ has no meaning in itself, “it seems to be able to do things in subtle and miraculous ways,” says Michael Rosen, poet and author. Consider the difference between ‘he scored a goal’ and ‘he scored the goal’. The inclusion of ‘the’ immediately signals something important about that goal. Perhaps it was the only one of the match? Or maybe it was the clincher that won the league? Context very often determines sense.

There are many exceptions regarding the use of the definite article, for example in relation to proper nouns. We wouldn’t expect someone to say ‘the Jonathan’ but it’s not incorrect to say ‘you’re not the Jonathan I thought you were’. And a football commentator might deliberately create a generic vibe by saying, ‘you’ve got the Lampards in midfield’ to mean players like Lampard.

The use of ‘the’ could have increased as trade and manufacture grew in the run-up to the industrial revolution, when we needed to be referential about things and processes. ‘The’ helped distinguish clearly and could act as a quantifier, for example, ‘the slab of butter’.

This could lead to a belief that ‘the’ is a workhorse of English; functional but boring. Yet Rosen rejects that view. While primary school children are taught to use ‘wow’ words, choosing ‘exclaimed’ rather than ‘said’, he doesn’t think any word has more or less ‘wow’ factor than any other; it all depends on how it’s used. “Power in language comes from context… ‘the’ can be a wow word,” he says.

This simplest of words can be used for dramatic effect. At the start of Hamlet, a guard’s utterance of ‘Long live the King’ is soon followed by the apparition of the ghost: ‘Looks it not like the King?’ Who, the audience wonders, does ‘the’ refer to? The living King or a dead King? This kind of ambiguity is the kind of ‘hook’ that writers use to make us quizzical, a bit uneasy even. “‘The’ is doing a lot of work here,” says Rosen.

Deeper meaning

‘The’ can even have philosophical implications. The Austrian philosopher Alexius Meinong said a denoting phrase like ‘the round square’ introduced that object; there was now such a thing. According to Meinong, the word itself created non-existent objects, arguing that there are objects that exist and ones that don’t – but they are all created by language. “‘The’ has a kind of magical property in philosophy,” says Barry C Smith, director of the Institute of Philosophy, University of London.

The British philosopher Bertrand Russell wrote a paper in 1905 called On Denoting, all about the definite article. Russell put forward a theory of definite descriptions. He thought it intolerable that phrases like ‘the man in the Moon’ were used as though they actually existed. He wanted to revise the surface grammar of English, as it was misleading and “not a good guide to the logic of the language”, explains Smith. This topic has been argued about, in a philosophical context, ever since. “Despite the simplicity of the word,” observes Thoms, “it’s been evading definition in a very precise way for a long time.”

Lynne Murphy, professor of linguistics at the University of Sussex, spoke at the Boring Conference in 2019, an event celebrating topics that are mundane, ordinary and overlooked, but are revealed to be fascinating. She pointed out how strange it is that our most commonly used word is one that many of the world’s languages don’t have. And how amazing English speakers are for getting to grips with the myriad ways in which it’s used.

Scandinavian languages such as Danish or Norwegian and some Semitic languages like Hebrew or Arabic use an affix (or a short addition to the end of a word) to determine whether the speaker is referring to a particular object or using a more general term. Latvian or Indonesian deploy a demonstrative – words like ‘this’ and ‘that’ – to do the job of ‘the’. There’s another group of languages that don’t use any of those resources, such as Urdu or Japanese.

Function words are very specific to each language.

So, someone who is a native Hindi or Russian speaker is going to have to think very differently when constructing a sentence in English. Murphy says that she has noticed, for instance, that sometimes her Chinese students hedge their bets and include ‘the’ where it is not required. Conversely, Smith describes Russian friends who are so unsure when to use ‘the’ that they sometimes leave a little pause: ‘I went into… bank. I picked up… pen.’ English speakers learning a language with no equivalent of ‘the’ also struggle and might overcompensate by using words like ‘this’ and ‘that’ instead.

Atlantic divide

Even within the language, there are subtle differences in how ‘the’ is used in British and American English, such as when talking about playing a musical instrument. An American might be more likely to say ‘I play guitar’ whereas a British person might opt for ‘I play the guitar’. But there are some instruments where both nationalities might happily omit ‘the’, such as ‘I play drums’. Equally the same person might interchangeably refer to their playing of any given instrument with or without the definite article – because both are correct and both make sense.

And yet, keeping with the musical vibe, there’s a subtle difference in meaning of ‘the’ in the phrases ‘I play the piano’ and ‘I clean the piano’. We instinctively understand the former to mean the piano playing is general and not restricted to one instrument, and yet in the latter we know that it is one specific piano that is being rendered spick and span.

Culpeper says ‘the’ occurs about a third less in spoken language. Though of course whether it is used more frequently in text or speech depends on the subject in question. A more personal, emotional topic might have fewer instances of ‘the’ than something more formal. ‘The’ appears most frequently in academic prose, offering a useful word when imparting information – whether it’s scientific papers, legal contracts or the news. Novels use ‘the’ least, partly because they have conversation embedded in them.

According to Culpeper, men say ‘the’ significantly more frequently. Deborah Tannen, an American linguist, has a hypothesis that men deal more in report and women more in rapport – this could explain why men use ‘the’ more often. Depending on context and background, in more traditional power structures, a woman may also have been socialised not to take the voice of authority so might use ‘the’ less frequently. Though any such gender-based generalisations also depend on the nature of the topic being studied.

Those in higher status positions also use ‘the’ more – it can be a signal of their prestige and (self) importance. And when we talk about ‘the prime minister’ or ‘the president’ it gives more power and authority to that role. It can also give a concept credibility or push an agenda. Talking about ‘the greenhouse effect’ or ‘the migration problem’ makes those ideas definite and presupposes their existence.

‘The’ can be a “very volatile” word, says Murphy. Someone who refers to ‘the Americans’ versus simply ‘Americans’ is more likely to be critical of that particular nationality in some capacity. When people referred to ‘the Jews’ in the build-up to the Holocaust, it became othering and objectifying. According to Murphy, “‘The’ makes the group seem like it’s a large, uniform mass, rather than a diverse group of individuals.” It’s why Trump was criticised for using the word in that context during a 2016 US presidential debate.

Origins

We don’t know exactly where ‘the’ comes from – it doesn’t have a precise ancestor in Old English grammar. The Anglo Saxons didn’t say ‘the’, but had their own versions. These haven’t completely died out, according to historical linguist Laura Wright. In parts of Yorkshire, Lancashire and Cumberland there is a remnant of Old English inflective forms of the definite article – t’ (as in “going t’ pub”).

The letter y in terms like ‘ye olde tea shop’ is from the old rune Thorn, part of a writing system used across northern Europe for centuries. It’s only relatively recently, with the introduction of the Roman alphabet, that ‘th’ has come into being.

‘The’ deserves to be celebrated. The three-letter word punches well above its weight in terms of impact and breadth of contextual meaning. It can be political, it can be dramatic – it can even bring non-existent concepts into being.

You can hear more about ‘the’ on BBC Radio 4’s Word of Mouth: The Most Powerful Word.

Hear What Scholars Think English Will Sound Like In 100 Years

Today’s English is the result of hundreds of years of evolution, so why would we not expect it to keep changing? Here’s what it might become by the 22nd century.

By Michael Erard

You might think of English, which is spoken by the largest number of people on the planet, as a mighty, never-ending river, full of life and always churning and changing. If you speak the language, it’s natural to wonder where this river is headed. And who will shape the sounds that bubble out of it in the future — 20, 50, or even 100 years from now?

Feeding the river are two tributaries that determine its direction. One of these carries the influence of the estimated two billion people who speak English as a non-native language. They are influential not just because of their number but also because the majority of interactions in English in the world occur between non-native speakers — as many as 80 percent, according to linguists. This is English playing its role as a global lingua franca, helping speakers of other languages connect with each other.

The other tributary carries the changes that English has been undergoing for hundreds of years. Between the 12th and 16th centuries, for example, English underwent the “great vowel shift,” which shortened some vowels, like “ee” to “aye,” and pushed others up and to the front of the mouth, so that the Middle English vowel pronounced “oh” is now pronounced “oo,” as in “boot.”

In the mid-20th century, linguist and English historian at the University of Michigan Albert Marckwardt argued that English wasn’t done changing and that the momentum of the past would carry on into the future. It’s true that some vowels seem durable; the pronunciation of “ship,” “bet,” “ox,” and “full” have been the same for centuries. But Marckwardt argued that some vowels are still going to shift. For example, the word “home” — pronounced “heim” in Germanic, “hahm” in Old English, and “hawm” in Middle English — might someday be “hoom.”On the other hand, he predicted that English consonants would remain largely the same, although some have already changed. For instance, the “k” in “knife” was once pronounced, “nature” was “natoor,” and “special” was “spe-see-al.” But for the most part, Marckwardt said, we shouldn’t expect to see much change in English consonants.

The success of English — especially the fact that it is used by many non-native English speakers — means, among other things, that the history of the language is no longer a reliable map about how its pronunciation might change. Consider, for instance, that a number of distinct regional variations of English are emerging around the world.

While all of this research gives us some tantalizing ideas about how English might sound in the future, it doesn’t tell us very much about when we might expect those changes. It could happen within a generation, but it could take another century. It mostly depends on which regional version of English becomes dominant, says Jennifer Jenkins. “Beyond that, I’d need a crystal ball to be able to say more.”

All this assumes that English will remain as predominant as it has been, even as it diverges into multiple Englishes, each one carving its own meandering path toward the sea.

One of them is in Southeast Asia. More than 10 years ago, linguist David Deterding recorded English teachers from Singapore, Vietnam, Laos, and Myanmar in order to identify notable features of their English. The first sound from the word “thing” was a popping “t,” “maybe” sounded like “mebbe,” and “place” became “pless.” Deterding also noticed that speakers laid more stress at the end of sentences (in the UK and U.S., such heavy stress marks new information in a sentence).

These sound changes were influenced by those teachers’ mother tongues. To some people’s ears, particularly those who speak British or American English, these pronunciations might sound wrong, as if the speakers had simply not worked hard enough to get rid of their accents. However, as Deterding pointed out, the teachers could still understand each other. So in what sense are these non-native accents a problem, especially if the speakers are mainly going to be talking to other non-native speakers?

All over the world, this question is something that teachers of English are working out for themselves. Is it better practice to promote intelligibility or should learners reproduce American- or British-accented English? The direction that is taken will determine how the English of the future sounds.

Interestingly, where Albert Marckwardt predicted that English vowels would see the biggest changes, others think it will be certain consonants that are drastically altered.

Jennifer Jenkins, a linguist at Southhampton University in the UK, has studied the communication breakdown between non-native speakers of English to see what pronunciations they stumble over. These provide a clue as to how English may change. The aspects of English pronunciation that promote intelligibility would tend to spread, she has said, while those that promote misunderstanding would wither away.

In contrast to Marckwardt, Jenkins’ findings suggest some severe changes ahead for consonants. For instance, she says the “th” of “thus” and “thin” are often dropped and replaced with either “s” and “z” or “t” and “d.” (In Europe, it’s looking like the “s” and “z” may win out.) Another consonant that causes problems is the “l” of “hotel” and “rail,” which speakers replace with a vowel or what’s known as a “clear l,” as in “lady.” (This is a pronunciation change that Chinese speakers of English often make.)

Jenkins also predicts that some clusters of consonants will simplify. At the beginning of words, they will survive, but at the end of words they may vanish. This means you may hear “bess” for “best” and “assep” for “accept.”

In the short term, these new pronunciations could become part of how English sounds on the tongues of people who use it as a lingua franca. But in the long term, they could filter into standard English in other parts of the world — even its homelands — if the innovations seem worth adopting.

Barbara Seidlhofer, a linguist at the University of Vienna in Austria who studies verbal interactions between non-native English speakers, has made some predictions about how words formed in these regional English varieties will affect how they sound. She has noted that non-native speakers do not distinguish between mass and count nouns, so someday we might talk about “informations” and “furnitures.”

Also, the third person singular (such as “she runs” or “he writes”) is the only English verb form with an “s” at the end. Seidlhofer has found non-native speakers drop this. They also simplify verb phrases, saying “I look forward to see you tomorrow” instead of “I am looking forward to seeing you tomorrow.”

25 maps that explain the English language

Source: http://www.vox.com/2015/3/3/8053521/25-maps-that-explain-english

English is the language of Shakespeare and the language of Chaucer. It’s spoken in dozens of countries around the world, from the United States to a tiny island named Tristan da Cunha. It reflects the influences of centuries of international exchange, including conquest and colonization, from the Vikings through the 21st century. Here are 25 maps and charts that explain how English got started and evolved into the differently accented languages spoken today.

1. Where English comes from

English, like more than 400 other languages, is part of the Indo-European language family, sharing common roots not just with German and French but with Russian, Hindi, Punjabi, and Persian. This beautiful chart by Minna Sundberg, a Finnish-Swedish comic artist, shows some of English’s closest cousins, like French and German, but also its more distant relationships with languages originally spoken far from the British Isles such as Farsi and Greek.

English, like more than 400 other languages, is part of the Indo-European language family, sharing common roots not just with German and French but with Russian, Hindi, Punjabi, and Persian. This beautiful chart by Minna Sundberg, a Finnish-Swedish comic artist, shows some of English’s closest cousins, like French and German, but also its more distant relationships with languages originally spoken far from the British Isles such as Farsi and Greek.

2. Where Indo-European languages are spoken in Europe today

Saying that English is Indo-European, though, doesn’t really narrow it down much. This map shows where Indo-European languages are spoken in Europe, the Middle East, and South Asia today, and makes it easier to see what languages don’t share a common root with English: Finnish and Hungarian among them.

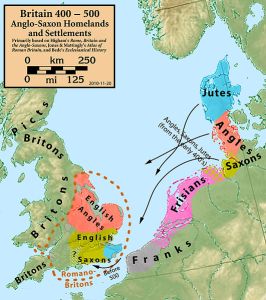

3. The Anglo-Saxon migration

Here’s how the English language got started: After Roman troops withdrew from Britain in the early 5th century, three Germanic peoples — the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes — moved in and established kingdoms. They brought with them the Anglo-Saxon language, which combined with some Celtic and Latin words to create Old English. Old English was first spoken in the 5th century, and it looks incomprehensible to today’s English-speakers. To give you an idea of just how different it was, the language the Angles brought with them had three genders (masculine, feminine, and neutral). Still, though the gender of nouns has fallen away in English, 4,500 Anglo-Saxon words survive today. They make up only about 1 percent of the comprehensive Oxford English Dictionary, but nearly all of the most commonly used words that are the backbone of English. They include nouns like “day” and “year,” body parts such as “chest,” arm,” and “heart,” and some of the most basic verbs: “eat,” “kiss,” “love,” “think,” “become.” FDR’s sentence “The only thing we have to fear is fear itself” uses only words of Anglo-Saxon origin.

Here’s how the English language got started: After Roman troops withdrew from Britain in the early 5th century, three Germanic peoples — the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes — moved in and established kingdoms. They brought with them the Anglo-Saxon language, which combined with some Celtic and Latin words to create Old English. Old English was first spoken in the 5th century, and it looks incomprehensible to today’s English-speakers. To give you an idea of just how different it was, the language the Angles brought with them had three genders (masculine, feminine, and neutral). Still, though the gender of nouns has fallen away in English, 4,500 Anglo-Saxon words survive today. They make up only about 1 percent of the comprehensive Oxford English Dictionary, but nearly all of the most commonly used words that are the backbone of English. They include nouns like “day” and “year,” body parts such as “chest,” arm,” and “heart,” and some of the most basic verbs: “eat,” “kiss,” “love,” “think,” “become.” FDR’s sentence “The only thing we have to fear is fear itself” uses only words of Anglo-Saxon origin.

Rest of the article and illustrations: http://www.vox.com/2015/3/3/8053521/25-maps-that-explain-english

In an effort to help those who may have been hit by the onslaught of marketing slurry that passes through the English language, every now and then, I will post some words or phrases that are absurd, unless you are in marketing, sales, or some other line of work where junking up the language is simply a way of life. To start, I submit two:

Free Gift. By its definition, a gift is free, at least to the recipient. If somebody gives you a gift that’s not free, then it is not a gift.

Truly Unique. Can something be falsely unique? Unique means one of a kind. Doesn’t matter if it is a good one of a kind, or a bad one of a kind, it is a one of a kind. If it is unique, by its definition it is true to itself because it is one of a kind.

It is a pity to live under a tax system where you must be smarter to figure out what you owe in taxes than the brain power it took to earn the money to begin with. I have a Master’s degree in English and have written for two small daily newspapers, two small national magazines, and have worked with scientists and engineers on technical documents and consumer documents, and the tax code is the worst cluster fubar of the English language that I have ever seen. It reads like it went through a meat grinder of politicians, lawyers (I know, any more using politician and lawyer in the same sentence is redundant), lobbyists (ubiquitous as cockroaches and also often lawyers) and bureaucrats, and what came out the other end would be suitable for use as secret code in any war. Nobody could decipher it. Not even us.

On top of that, you can get advise from an IRS representative, but it’s not legally binding.

I’m not a TEA party activist, but doing your taxes should not be an industry all to itself with preparers acting like the oracles at Delphi, or a chore, if done by yourself, relegated to the level of near madness.

Filed under Random Access Thoughts, taxes, words, writing