Source: Dashiell Hammett: a hero for our time – San Francisco Chronicle

Every Christmas season, my family indulges in the same movie-watching rituals as we trim the tree and string necklaces of twinkling lights around the living room. These movies serve as a comforting backdrop to our yuletide routines. Some of our favorite seasonal films are relative obscurities like “The Family Man” (2000), starring Nicolas Cage, Téa Leoni and Don Cheadle. But we also search out classics, including movies that seemingly have nothing to do with the holiday season. Inevitably, we end up watching at least one of the old “Thin Man” features, that durable Dashiell Hammett detective series starring the most adorable and effervescent married couple in cinematic history, Nick and Nora Charles (William Powell and Myrna Loy).

Why does “The Thin Man” series beckon us this time of year? Maybe it’s the lovely, icy clatter of a holiday martini shaker, that merry clinking sound Nora used to call Nick home to their New York hotel suite when he was relaxing far away in Central Park with their toddler. “Nicky,” the bibulous detective tells Junior, “something tells me that something important is happening somewhere and I think we should be there.”

Or maybe it’s the witty banter and teasing sexuality between Nick and Nora that every sophisticated relationship should aspire to. Nick (trying to divert his wife from an uncomfortably racy subject): “Did I ever tell you that you’re the most fascinating woman on this side of the Rockies?” Nora (signaling she’s no prude): “Wait till you see me on the other side.”

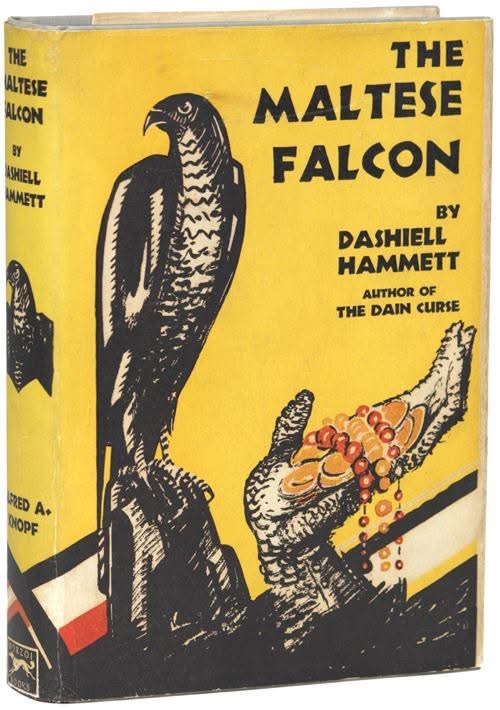

Or it could be the San Francisco aura that drifts through the “Thin Man” films, especially my favorite, “After the Thin Man” (1936), which is set in the city and features locations like the Coit Tower lawn, doubling as the grounds of the Charleses’ Telegraph Hill mansion. Foggy nights in San Francisco are still suffused with a Hammett-like mystery. And there is no better place to conjure the spirit of the founder of the hard-boiled mystery genre than John’s Grill on Ellis Street, where Hammett hero Sam Spade grabbed a quick meal of chops, baked potato and sliced tomato in “The Maltese Falcon.” Hammett himself pounded out his pulp masterpieces on his Underwood typewriter in his apartment nearby, at 891 Post St., after his TB-wracked lungs made it impossible for him to continue his career as a Pinkerton Agency gumshoe.

There is no better way to celebrate the holidays in San Francisco than taking a break from the tyranny of shopping at the legendary downtown grill, presided over by John Konstin, the city’s most charming Greek (besides Art Agnos). A recent lunch hour there was populated by the usual mix of jailhouse lawyers, newshounds, colorful barflies, and SFPD detectives with legendary names – including Lt. Dave Falzon and retired homicide inspector John Cleary Jr. In other words, old San Francisco at its best.

And there is no better lunch companion for such an occasion than fedora-wearing, dapper Eddie Muller — the “Czar of Noir” whose classic cinema festival at the Castro Theatre each January brings together a wildly diverse pageant of filmgoers, from schlumpy and frighteningly obsessive cineastes to elegantly dressed lounge-room lizards and femme fatales who have stepped right out of their own torrid dream. Muller is also a growing presence on the Turner Classic Movies channel, as the film noir host for the brilliantly curated network.

Muller has a familial affinity for the world of Hammett. His late father was the boxing reporter for the San Francisco Examiner for a half-century, a respected fixture in a demimonde filled with the palookas, promoters, and gangsters — the same types Nick and Nora liked to pal around with. And we both share an affection for the prototypical, if opposite, Hammett screen heroines, Loy and Mary Astor.

Astor was the sad-eyed, seductive screen siren who costarred with Bogart in “The Maltese Falcon” (and with my father, Lyle, in such lesser 1930s offerings as “Return of the Terror,” “Red Hot Tires” and “Trapped by Television,” a B-movie thriller that foresaw the scary aspects of the coming medium). Astor was a sexually liberated woman of her day; her erotic self-confidence surges through her performance as the masterfully manipulative Brigid O’Shaughnessy in the Hammett classic.

In 1936, Astor found herself on the pyre in the hottest Hollywood sex scandal of its day, when her estranged husband exposed her “Purple Diary” to the press — a lusty account of her sexual exploits, including the grades she assigned to her lovers’ performances. Playwright George S. Kaufman scored the highest, with Astor extolling his prowess. “Fits me perfectly,” she wrote. “Many exquisite moments … twenty — count them, diary, twenty … I don’t see how he does it … he’s perfect.”

Astor — whose Purple Diary is the subject of two recent books, including a sensually illustrated chronicle by the artist Edward Sorel — got Muller and me talking about Hammett and his view of women. “In some ways, the male-female dynamic is the most interesting thing about Hammett’s work,” said Muller, between sips from his Manhattan. “There’s an emotional complexity and tension that separates it from other detective fiction.” In his own life, Hammett cut himself off from his father and brother at a young age, but remained close to his mother and sister. His own formidable drinking and sparring partner, the writer Lillian Hellman, was the inspiration for Nora Charles.

“He was a tall, slim, well-dressed ladies’ man, who carried with him a sense of damage that women found attractive,” continued Muller. “His drinking, his illness. He made binge drinking heroic because he was so frail. Women would marvel at him — it’s 4 a.m. and he’s still going.”

Hammett had another kind of fortitude as well. A lifelong man of the Left, he was dragged before a federal tribunal during the Cold War and asked to reveal the names of those who had contributed to a bail fund he had overseen for jailed Communist Party leaders. He refused. Ratting on friends was not the kind of thing that the creator of Sam Spade would do. He was sentenced to six months in federal prison for contempt of court, and when he was released in December 1951, his health was more ruined than ever. In 1953, he was summoned again by the witch-hunters, this time by Sen. Joe McCarthy and his sidekick, the reptilian Roy Cohn — one of Donald Trump’s mentors. Again Hammett refused to cooperate. He was blacklisted by Hollywood and went broke. But he was unbroken.

As Trump adviser Newt Gingrich floats the idea of reviving the notorious House Un-American Activities Committee, it’s a good time for us to recall Hammett’s heroism. “People should read his testimony and look at the pictures of him as he underwent the inquisition; it’s so inspiring,” said Muller. “He was just so cool and unshakable. His attitude was like, ‘Do your worst, you can’t even make me angry.’ He was one of his own heroes come to life.”

San Francisco Chronicle columnist David Talbot appears Sundays, Tuesdays and Thursdays. Email: dtalbot@sfchronicle.com