Bertrand Russell’s magnificent Nobel prize acceptance speech.

Maria Popova

Bertrand Russell (May 18, 1872–February 2, 1970) endures as one of humanity’s most lucid and luminous minds — an oracle of timeless wisdom on everything from what “the good life” really means to why “fruitful monotony” is essential for happiness to love, sex, and our moral superstitions. In 1950, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature for “his varied and significant writings in which he champions humanitarian ideals and freedom of thought.” On December 11 of that year, 78-year-old Russell took the podium in Stockholm to receive the grand accolade.

Later included in Nobel Writers on Writing (public library) — which also gave us Pearl S. Buck, the youngest woman to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature, on art, writing, and the nature of creativity — his acceptance speech is one of the finest packets of human thought ever delivered from a stage.

Russell begins by considering the central motive driving human behavior:

All human activity is prompted by desire. There is a wholly fallacious theory advanced by some earnest moralists to the effect that it is possible to resist desire in the interests of duty and moral principle. I say this is fallacious, not because no man ever acts from a sense of duty, but because duty has no hold on him unless he desires to be dutiful. If you wish to know what men will do, you must know not only, or principally, their material circumstances, but rather the whole system of their desires with their relative strengths.

[…]

Man differs from other animals in one very important respect, and that is that he has some desires which are, so to speak, infinite, which can never be fully gratified, and which would keep him restless even in Paradise. The boa constrictor, when he has had an adequate meal, goes to sleep, and does not wake until he needs another meal. Human beings, for the most part, are not like this.

Russell points to four such infinite desires — acquisitiveness, rivalry, vanity, and love of power — and examines them in order:

Acquisitiveness — the wish to possess as much as possible of goods, or the title to goods — is a motive which, I suppose, has its origin in a combination of fear with the desire for necessaries. I once befriended two little girls from Estonia, who had narrowly escaped death from starvation in a famine. They lived in my family, and of course had plenty to eat. But they spent all their leisure visiting neighbouring farms and stealing potatoes, which they hoarded. Rockefeller, who in his infancy had experienced great poverty, spent his adult life in a similar manner.

[…]

However much you may acquire, you will always wish to acquire more; satiety is a dream which will always elude you.

In 1938, Henry Miller also articulated this fundamental driver in his brilliant meditation on how money became a human fixation. Decades later, modern psychologists would term this notion “the hedonic treadmill.” But for Russell, this elemental driver is eclipsed by an even stronger one — our propensity for rivalry:

The world would be a happier place than it is if acquisitiveness were always stronger than rivalry. But in fact, a great many men will cheerfully face impoverishment if they can thereby secure complete ruin for their rivals. Hence the present level of taxation.

Rivalry, he argues, is in turn upstaged by human narcissism. In a sentiment doubly poignant in the context of today’s social media, he observes:

Vanity is a motive of immense potency. Anyone who has much to do with children knows how they are constantly performing some antic, and saying “Look at me.” “Look at me” is one of the most fundamental desires of the human heart. It can take innumerable forms, from buffoonery to the pursuit of posthumous fame.

[…]

It is scarcely possible to exaggerate the influence of vanity throughout the range of human life, from the child of three to the potentate at whose frown the world trembles.

But the most potent of the four impulses, Russell argues, is the love of power:

Love of power is closely akin to vanity, but it is not by any means the same thing. What vanity needs for its satisfaction is glory, and it is easy to have glory without power… Many people prefer glory to power, but on the whole these people have less effect upon the course of events than those who prefer power to glory… Power, like vanity, is insatiable. Nothing short of omnipotence could satisfy it completely. And as it is especially the vice of energetic men, the causal efficacy of love of power is out of all proportion to its frequency. It is, indeed, by far the strongest motive in the lives of important men.

[…]

Love of power is greatly increased by the experience of power, and this applies to petty power as well as to that of potentates.

Anyone who has ever agonized in the hands of a petty bureaucrat — something Hannah Arendt unforgettably censured as a special kind of violence — can attest to the veracity of this sentiment. Russell adds:

In any autocratic regime, the holders of power become increasingly tyrannical with experience of the delights that power can afford. Since power over human beings is shown in making them do what they would rather not do, the man who is actuated by love of power is more apt to inflict pain than to permit pleasure.

But Russell, a thinker of exceptional sensitivity to nuance and to the dualities of which life is woven, cautions against dismissing the love of power as a wholesale negative driver — from the impulse to dominate the unknown, he points out, spring such desirables as the pursuit of knowledge and all scientific progress. He considers its fruitful manifestations:

It would be a complete mistake to decry love of power altogether as a motive. Whether you will be led by this motive to actions which are useful, or to actions which are pernicious, depends upon the social system, and upon your capacities. If your capacities are theoretical or technical, you will contribute to knowledge or technique, and, as a rule, your activity will be useful. If you are a politician you may be actuated by love of power, but as a rule this motive will join itself on to the desire to see some state of affairs realized which, for some reason, you prefer to the status quo.

Russell then turns to a set of secondary motives. Echoing his enduring ideas on the interplay of boredom and excitement in human life, he begins with the notion of love of excitement:

Human beings show their superiority to the brutes by their capacity for boredom, though I have sometimes thought, in examining the apes at the zoo, that they, perhaps, have the rudiments of this tiresome emotion. However that may be, experience shows that escape from boredom is one of the really powerful desires of almost all human beings.

He argues that this intoxicating love of excitement is only amplified by the sedentary nature of modern life, which has fractured the natural bond between body and mind. A century after Thoreau made his exquisite case against the sedentary lifestyle, Russell writes:

Our mental make-up is suited to a life of very severe physical labor. I used, when I was younger, to take my holidays walking. I would cover twenty-five miles a day, and when the evening came I had no need of anything to keep me from boredom, since the delight of sitting amply sufficed. But modern life cannot be conducted on these physically strenuous principles. A great deal of work is sedentary, and most manual work exercises only a few specialized muscles. When crowds assemble in Trafalgar Square to cheer to the echo an announcement that the government has decided to have them killed, they would not do so if they had all walked twenty-five miles that day. This cure for bellicosity is, however, impracticable, and if the human race is to survive — a thing which is, perhaps, undesirable — other means must be found for securing an innocent outlet for the unused physical energy that produces love of excitement… I have never heard of a war that proceeded from dance halls.

[…]

Civilized life has grown altogether too tame, and, if it is to be stable, it must provide harmless outlets for the impulses which our remote ancestors satisfied in hunting… I think every big town should contain artificial waterfalls that people could descend in very fragile canoes, and they should contain bathing pools full of mechanical sharks. Any person found advocating a preventive war should be condemned to two hours a day with these ingenious monsters. More seriously, pains should be taken to provide constructive outlets for the love of excitement. Nothing in the world is more exciting than a moment of sudden discovery or invention, and many more people are capable of experiencing such moments than is sometimes thought.

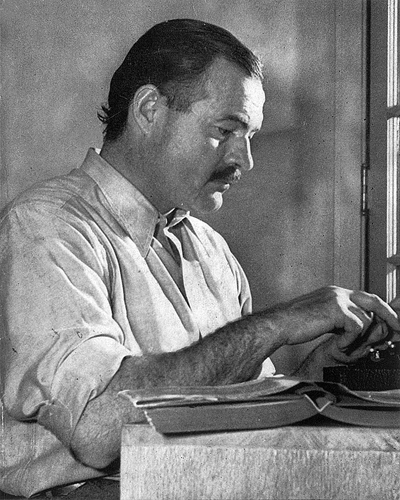

Complement Nobel Writers on Writing with more excellent Nobel Prize acceptance speeches — William Faulkner on the artist as a booster of the human heart, Ernest Hemingway on writing and solitude, Alice Munro on the secret to telling a great story, and Saul Bellow on how literature ennobles the human spirit — then revisit Russell on immortality and why science is the key to democracy.