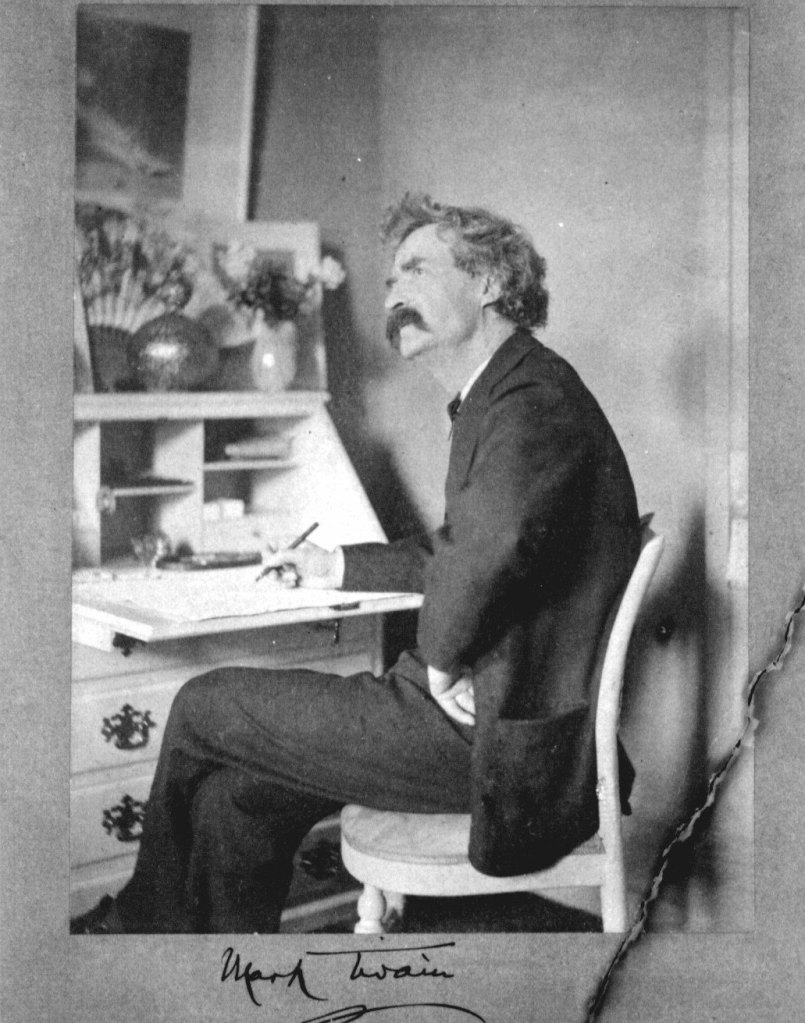

“Delicacy–a sad, sad false delicacy–robs literature of the two best things among its belongings: Family-circle narratives & obscene stories.” – Letter to W. D. Howells, 9/19/1877

“Delicacy–a sad, sad false delicacy–robs literature of the two best things among its belongings: Family-circle narratives & obscene stories.” – Letter to W. D. Howells, 9/19/1877

Filed under 2025, author, author commentary

Author

Author, dear author, /

I relent, I repent, I plead: /

“Give me one more chance!”

.

.

#051125 #2025 #author #relent #repent #plead #chance #haiku #poem #poetry #haiga #tomgould #cartoonnotmine #may #sunday

Filed under 2025, author, Cartoon, haiku, poem, poet, poetry, poetry by author, Poetry by David E. Booker, writer

“As long as they talk about you, you’re not really dead, as long as they speak your name, you continue. A legend doesn’t die, just because the man dies.”

AS I KNEW HIM: My Dad Rod Serling

Filed under author, author commentary, Uncategorized

Saved

My giblets were saved /

by buckling up. Gravy,

however, was lost.

.

.

#giblets #buckling #gravy #lost #photo #poem #poetry #haiku #haiga #davidebooker #knoxville #november #friday #112423 #2023

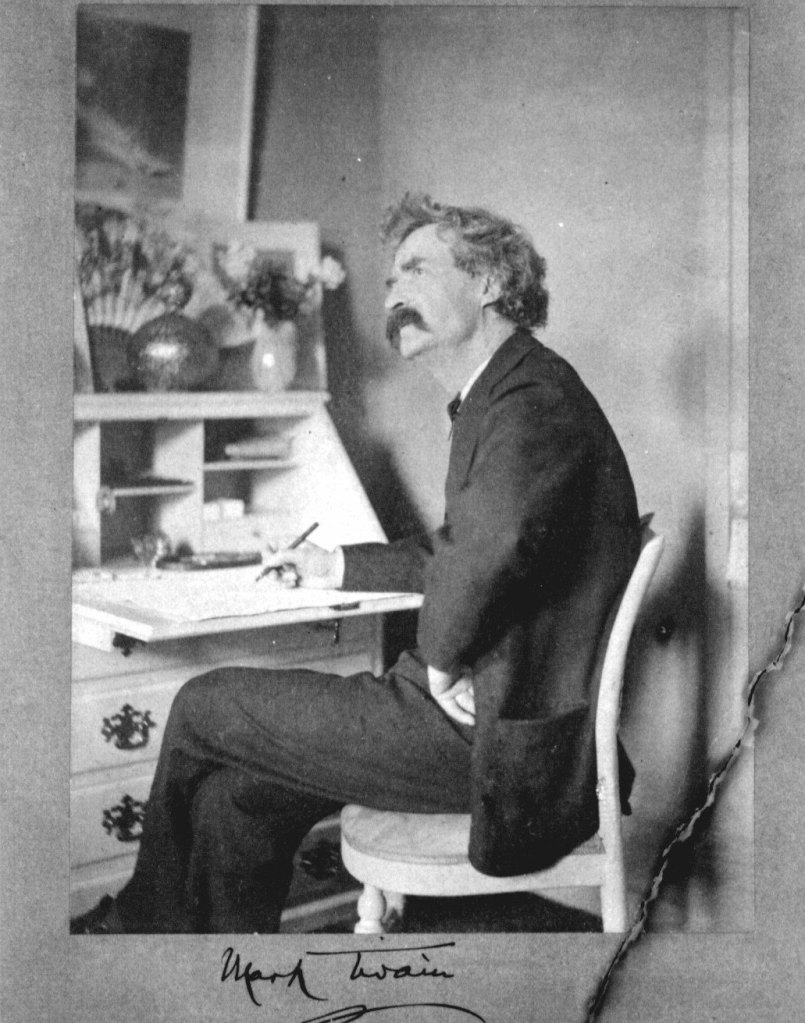

At 40, Franz Kafka (1883-1924), who never married and had no children, walked through the park in Berlin when he met a girl who was crying because she had lost her favourite doll. She and Kafka searched for the doll unsuccessfully.

Kafka told her to meet him there the next day and they would come back to look for her.

The next day, when they had not yet found the doll, Kafka gave the girl a letter “written” by the doll saying “please don’t cry. I took a trip to see the world. I will write to you about my adventures.”

Thus began a story which continued until the end of Kafka’s life.

During their meetings, Kafka read the letters of the doll carefully written with adventures and conversations that the girl found adorable.

Finally, Kafka brought back the doll (he bought one) that had returned to Berlin.

“It doesn’t look like my doll at all,” said the girl.

Kafka handed her another letter in which the doll wrote: “my travels have changed me.” the little girl hugged the new doll and brought the doll with her to her happy home.

A year later Kafka died.

Many years later, the now-adult girl found a letter inside the doll. In the tiny letter signed by Kafka it was written:

“Everything you love will probably be lost, but in the end, love will return in another way.”

Embrace the change. It’s inevitable for growth. Together we can shift pain into wonder and love, but it is up to us to consciously and intentionally create that connection.

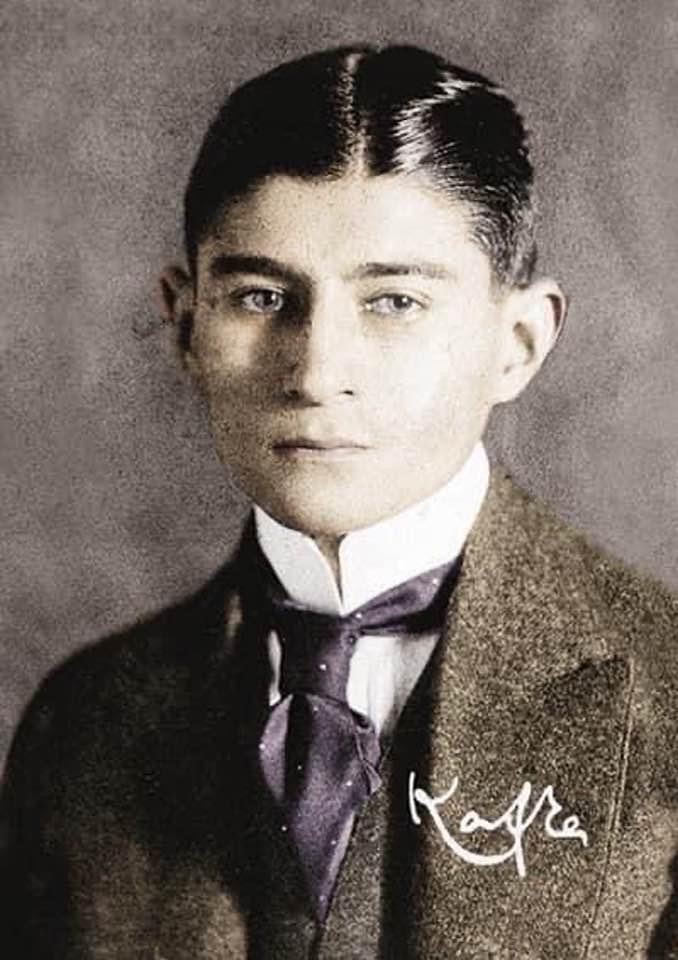

New technology is helping archaeologists uncover details of the playwright’s home, workplaces and his final resting place.

William Shakespeare is widely regarded as one of the greatest authors of all time and one of the most important and influential people who has ever lived. His written works (plays, sonnets and poems) have been translated into more than 100 languages and these are performed around the world.

There is also an enduring desire to learn more about the man himself. Countless books and articles have been written about Shakespeare’s life. These have been based primarily on the scholarly analysis of his works and the official record associated with him and his family. Shakespeare’s popularity and legacy endures, despite uncertainties in his life story and debate surrounding his authorship and identity.

The life and times of William Shakespeare and his family have also recently been informed by cutting-edge archaeological methods and interdisciplinary technologies at both New Place (his long-since demolished family home) and his burial place at Holy Trinity Church, Stratford-upon-Avon. The evidence gathered from these investigations by the Centre of Archaeology at Staffordshire University provides new insights into his interests, attitudes and motivations – and those of his family – and shows how archaeology can provide further tangible evidence. These complement traditional Shakespearean research methods that have been limited to sparse documentary evidence and the study of his works.

Archaeology has the ability to provide a direct connection to an individual through the places and objects associated with them. Past excavations of the Shakespearean-era theatres in London have provided evidence of the places he worked and spent much of his time.

Attributing objects to Shakespeare is difficult, we have his written work of course, his portrait(s) and memorial bust – but all of his known possessions, like those mentioned in his will, no longer exist. A single gold signet ring, inscribed with the initials W S, is thought by some to be the most significant object owned and used by the poet, despite its questionable provenance.

Shakespeare’s greatest and most expensive possession was his house, New Place. Evidence, obtained through recent archaeological investigations of its foundations, give us quantifiable insights into Shakespeare’s thought processes, personal life and business success.

The building itself was lost in the 18th century, but the site and its remains were preserved beneath a garden. Erected in the centre of Stratford-upon-Avon more than a century prior to Shakespeare’s purchase in 1597, from its inception, it was architecturally striking. One of the largest domestic residences in Stratford, it was the only courtyard-style, open-hall house within the town.

This type of house typified the merchant and elite classes and in purchasing and renovating it to his own vision, Shakespeare inherited the traditions of his ancestors while embracing the latest fashions. The building materials used, its primary structure and later redevelopment can all be used as evidence of the deliberate and carefully considered choices made by him and his family.

Shakespeare focused on the outward appearance of the house, installing a long gallery and other fashionable architectural embellishments as was expected of a well-to-do, aspiring gentleman of the time. Many other medieval features were retained and the hall was likely retained as the showpiece of his home, a place to announce his prosperity, and his rise in status.

It provided a place for him and his immediate and extended family to live, work and entertain. But it was also a place which held local significance and symbolic associations. Intriguingly, its appearance also resembled the courtyard inn theatres of London and elsewhere with which Shakespeare was so familiar, presenting the opportunity to host private performances.

Extensive evidence of the personal possessions, diet and the leisure activities of Shakespeare, his family and the inhabitants of New Place were recovered during the archaeological investigations, revolutionising what we understand about his day-to-day life.

An online exhibition, due to be made available in early May 2020, presents 3D-scanned artefacts recovered at the site of New Place. These objects, some of which may have belonged to Shakespeare, have been chosen to characterise the chronological development and activities undertaken at the site.

Open access to these virtual objects will enable the dissemination of these important results and the potential for others to continue the research.

Archaeological evidence recovered from non-invasive investigations at Shakespeare’s burial place has also been used to provide further evidence of his personal and family belief. Multi-frequency Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) was used to investigate the Shakespeare family graves below the chancel of Holy Trinity Church.

A number of legends surrounded Shakespeare’s burial place. Among these were doubts over the presence of a grave, its contents, tales of grave robbing and suggestions of a large family crypt. The work confirmed that individual shallow graves exist beneath the tombstones and that the various members of Shakespeare’s family were not buried in coffins, but in simple shrouds. Analysis concluded that Shakespeare’s grave had been disturbed in the past and that it was likely that his skull had been removed, confirming recorded stories.

These family graves occupy a significant (and expensive) location in Holy Trinity Church. Despite this, the simple nature of Shakespeare’s grave, with no elite trappings or finery and no large family crypt, coupled with his belief that he should not be disturbed, confirm a simple regional practice based on pious religious observance and an affinity with his hometown.

There is still so much we don’t know about Shakespeare’s life, so it’s a safe bet that researchers will continue to investigate what evidence there is. Archaeological techniques can provide quantifiable information that isn’t available through traditional Shakespearean research. But just like other disciplines, interpretation – based on the evidence – will be key to unlocking the mysteries surrounding the life (and death) of the English language’s greatest writer.

William Mitchell is a Lecturer in Archaeology at Staffordshire University.

Filed under 2020, author, author profile

When Gabriel García Márquez’s most famous novel was published 50 years ago, it faced a difficult publishing climate and baffled reviews.

Source: The Unlikely Success of ‘One Hundred Years of Solitude’ – The Atlantic

In 1967, Sudamericana Press published One Hundred Years of Solitude (Cien años de soledad), a novel written by a little known Colombian author named Gabriel García Márquez. Neither the writer nor the publisher expected much of the book. They knew, as the publishing giant Alfred A. Knopf once put it, that “many a novel is dead the day it is published.” Unexpectedly, One Hundred Years of Solitude went on to sell over 45 million copies, solidified its stature as a literary classic, and garnered García Márquez fame and acclaim as one of the greatest Spanish-language writers in history.

Fifty years after the book’s publication, it may be tempting to believe its success was as inevitable as the fate of the Buendía family at the story’s center. Over the course of a century, their town of Macondo was the scene of natural catastrophes, civil wars, and magical events; it was ultimately destroyed after the last Buendía was born with a pig’s tail, as prophesied by a manuscript that generations of Buendías tried to decipher. But in the 1960s, One Hundred Years of Solitude was not immediately recognized as the Bible of the style now known as magical realism, which presents fantastic events as mundane situations. Nor did critics agree that the story was really groundbreaking. To fully appreciate the novel’s longevity, artistry, and global resonance, it is essential to examine the unlikely confluence of factors that helped it overcome a difficult publishing climate and the author’s relative anonymity at the time.

* * *

In 1965, the Argentine Sudamericana Press was a leading publisher of contemporary Latin American literature. Its acquisitions editor, in search of new talent, cold-called García Márquez to publish some of his work. The writer replied with enthusiasm that he was working on One Hundred Years of Solitude, “a very long and very complex novel in which I have placed my best illusions.” Two and a half months before the novel’s release in 1967, García Márquez’s enthusiasm turned into fear. After mistaking an episode of nervous arrhythmia for a heart attack, he confessed in a letter to a friend, “I am very scared.” What troubled him was the fate of his novel; he knew it could die upon its release. His fear was based on a harsh reality of the publishing industry for rising authors: poor sales. García Márquez’s previous four books had sold fewer than 2,500 copies in total.

The best that could happen to One Hundred Years of Solitude was to follow a path similar to the books released in the 1960s as part of the literary movement known as la nueva novela latinoamericana. Success as a new Latin American novel would mean selling its modest first edition of 8,000 copies in a region with 250 million people. Good regional sales would attract a mainstream publisher in Spain that would then import and publish the novel. International recognition would follow with translations into English, French, German, and Italian. To hit the jackpot in 1967 was to also receive one of the coveted literary awards of the Spanish language: the Biblioteca Breve, Rómulo Gallegos, Casa de las Américas, and Formentor.

This was the path taken by new Latin American novels of the 1960s such as Explosion in a Cathedral by Alejo Carpentier, The Time of the Hero by Mario Vargas Llosa, Hopscotch by Julio Cortázar, and The Death of Artemio Cruz by Carlos Fuentes. One Hundred Years of Solitude, of course, eclipsed these works on multiple fronts. Published in 44 languages, it remains the most translated literary work in Spanish after Don Quixote, and a survey among international writers ranks it as the novel that has most shaped world literature over the past three decades.

And yet it would be wrong to credit One Hundred Years of Solitude with starting a literary revolution in Latin America and beyond. Sudamericana published it when the new Latin American novel, by then popularly called the boom latinoamericano, had reached its peak in worldwide sales and influence. From 1961 onward, like a revived Homer, the almost blind Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges toured the planet as a literary celebrity. Following in his footsteps were rising stars like José Donoso, Cortázar, Vargas Llosa, and Fuentes. The international triumph of the Latin American Boom came when the Nobel Prize in Literature was awarded to Miguel Ángel Asturias in 1967. One Hundred Years of Solitude could not have been published in a better year for the new Latin American novel. Until then, García Márquez and his work were practically invisible.

* * *

In the decades before it reached its zenith, the new Latin American novel vied for attention alongside other literary trends in the region, Spain, and internationally. Its primary competition in Latin America was indigenismo, which wanted to give voice to indigenous peoples and was supported by many writers from the 1920s onward, including a young Asturias and José María Arguedas, who wrote in Spanish and Quechua, a native language of the Andes.

In Spain during the 1950s and 1960s, writers embraced social realism, a style characterized by terse stories of tragic characters at the mercy of dire social conditions. Camilo José Cela and Miguel Delibes were among its key proponents. Latin Americans wanting a literary career in Spain had to comply with this style, one example being a young Vargas Llosa living in Madrid, where he first wrote social-realist short stories.

Internationally, Latin American writers saw themselves competing with the French nouveau roman or “new novel.” Supporters, including Jean-Paul Sartre, praised it as the “anti-novel.” For them, the goal of literature was not narrative storytelling, but to serve as a laboratory for stylistic experiments. The most astonishing of such experiments was George Perec’s 1969 novel A Void, written without ever using the letter “e,” the most common in the French language.

In 1967, the book market was finally ready, it seemed, for One Hundred Years of Solitude. By then, mainstream Latin American writers had grown tired of indigenismo, a style used by “provincials of folk obedience,” as Cortázar scoffed. A young generation of authors in Spain belittled the stories in social-realist novels as predictable and technically unoriginal. And in France, emerging writers (such as Michel Tournier in his 1967 novel Vendredi) called for a return to narrative storytelling as the appeal of the noveau roman waned.

Between 1967 and 1969, reviewers argued that One Hundred Years of Solitude overcame the limitations of these styles. Contrary to the localism of indigenismo, reviewers saw One Hundred Years of Solitude as a cosmopolitan story, one that “could correct the path of the modern novel,” according to the Latin American literary critic Ángel Rama. Unlike the succinct language of social realism, the prose of García Márquez was an “atmospheric purifier,” full of poetic and flamboyant language, as the Spanish writer Luis Izquierdo argued. And contrary to the formal experiments of the nouveau roman, his novel returned to “the narrative of imagination,” as the Catalan poet Pere Gimferrer explained. Upon the book’s translation to major languages, international reviewers acknowledged this, too. The Italian writer Natalia Ginzburg forcefully called One Hundred Years of Solitude “an alive novel,” assuaging contemporary fears that the form was in crisis.

And yet these and other reviewers also remarked that One Hundred Years of Solitude was not a revolutionary work, but an anachronistic and traditionalist one, whose opening sentence resembled the “Once upon a time” formula of folk tales. And rather than a serious novel, it was a “comic masterpiece,” as an anonymous Times Literary Supplement reviewer wrote in 1967. Early views on this novel were indeed different from the ones that followed. In 1989, Yale literary scholar Harold Bloom solemnly called it “the new Don Quixote” and the writer Francine Prose confessed in 2013 that “One Hundred Years of Solitude convinced me to drop out of Harvard graduate school.”

Nowadays scholars, critics, and general readers mainly praise the novel as “the best expression of magical realism.” By 1995, magical realism was seen as making its way into the works of major English-language authors such John Updike and Salman Rushdie and moreover presented as “an inextricable, ineluctable element of human existence,” according to the New York Times literary critic Michiko Kakutani. But in 1967, the term magical realism was uncommon, even in scholarly circles. During One Hundred Years of Solitude’s first decade or so, to make sense of this “unclassifiable work,” as a reviewer put it, readers opted for labeling it as a mixture of “fantasy and reality,” “a realist novel full of imagination,” “a curious case of mythical realism,” “suprarrealism,”or, as a critic for Le Monde called it, “the marvelous symbolic.”

Now seen as a story that speaks to readers around the world, One Hundred Years of Solitude was originally received as a story about Latin America. The Harvard scholar Robert Kiely called it “a South American Genesis” in his review for the New York Times. Over the years, the novel grew to have “a texture of its own,” to use Updike’s words, and it became less a story about Latin America and more about mankind at large. William Kennedy wrote for the National Observer that it is “the first piece of literature since the Book of Genesis that should be required reading for the entire human race.” (Kennedy also interviewed García Márquez for a feature story, “The Yellow Trolley Car in Barcelona, and Other Visions,” published in The Atlantic in 1973.)

Perhaps even more surprisingly, respected writers and publishers were among the many and powerful detractors of this novel. Asturias declared that the text of One Hundred Years of Solitude plagiarized Balzac’s 1834 novel The Quest of the Absolute. The Mexican poet and Nobel recipient, Octavio Paz, called it “watery poetry.” The English writer Anthony Burgess claimed it could not be “compared with the genuinely literary explorations of Borges and [Vladimir] Nabokov.” Spain’s most influential literary publisher in the 1960s, Carlos Barral, not only refused to import the novel for publication, but he also later wrote “it was not the best novel of its time.” Indeed, entrenched criticism helps to make a literary work like One Hundred Years of Solitude more visible to new generations of readers and eventually contributes to its consecration.

With the help of its detractors, too, 50 years later the novel has fully entered popular culture. It continues to be read around the world, by celebrities such as Oprah Winfrey and Shakira, and by politicians such as Presidents Bill Clinton and Barack Obama, who called the book “one of my favorites from the time I was young.”

More recently, with the aid of ecologically minded readers and scholars, One Hundred Years of Solitude has unexpectedly gained renewed significance as awareness of climate change increases. After the explosion of the BP drilling rig Deepwater Horizon in 2010 in the Gulf of Mexico (one of the worst accidental environmental catastrophes in history), an environmental-policy advocate referred to the blowout as “tragic realism” and a U.S. journalist called it the “pig’s tail of the Petro-World.” What was the connection with One Hundred Years of Solitude? The explosion occurred at an oil and gas prospect named Macondo by a group of BP engineers two years earlier, so when Deepwater Horizon blew up, reality caught up with fiction. Some readers and scholars started to claim the spill revealed a prophecy similar to the one hidden in the Buendías manuscript: a warning about the dangers of humans’ destruction of nature.

García Márquez lived to see the name of Macondo become part of a significant, if horrifying, part of earth’s geological history, but not to celebrate the 50th anniversary of his masterpiece: He passed away in 2014. But the anniversary of his best known novel will be celebrated globally. As part of the commemoration, the Harry Ransom Center in Austin, Texas, where García Márquez’s archives have been kept since 2015, has opened an online exhibit of unique materials. Among the contents will be the original typescript of the “very long and very complex novel” that did not die but attained immortality the day it was published.

We want to hear what you think about this article. Submit a letter to the editor or write to letters@theatlantic.com.

Alvaro Santana-Acuña is an assistant professor of sociology at Whitman College. He is the author of the forthcoming book Ascent to Glory: The Transformation of One Hundred Years of Solitude Into a Global Classic.

Filed under 2020, author, author tribute

Alison Flood and Sian CainFri 10 Jan 2020 00.45 EST

Source: John le Carré wins $100,000 prize for ‘contribution to democracy’ | Books | The Guardian

John le Carré has been named the latest recipient of the $100,000 (£76,000) Olof Palme prize, an award given for an “outstanding achievement” in the spirit of the assassinated Swedish prime minister.

Won in the past by names including whistleblower Daniel Ellsberg, who exposed the US government’s secret intelligence about the Vietnam war in 1971, the Olof Palme prize is intended to reward “an outstanding achievement in any of the areas of anti-racism, human rights, international understanding, peace and common security”.

Announcing Le Carré’s win early on Friday morning, the prize organisers praised the 88-year-old author, whose real name is David Cornwell, “for his engaging and humanistic opinion-making in literary form regarding the freedom of the individual and the fundamental issues of mankind.

“Attracting worldwide attention, he is constantly urging us to discuss the cynical power games of the major powers, the greed of global corporations, the irresponsible play of corrupt politicians with our health and welfare, the growing spread of international crime, the tension in the Middle East and the alarming rise of fascism and xenophobia in Europe and the US,” the organisers said, calling his career “an extraordinary contribution to the necessary fight for freedom, democracy and social justice”.

Le Carré said he would donate the winnings to the international humanitarian NGO Médecins Sans Frontières.

Le Carré, the acclaimed author of some of the last century’s most enduring works, from Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy to The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, has been consistently outspoken about abuses of power in his fiction, his targets including governments, big pharma and arms dealing. Agent Running in the Field, his most recent book – which he has hinted will be his last – depicts collusion between Donald Trump’s US and the British security services with the aim of undermining the European Union.

The author has long steered clear of honours. In 2011, when he was nominated for the Man Booker International prize, he asked for his name to be withdrawn, saying that while he was “enormously flattered”, he did not compete for literary prizes.

Few authors have won the Olof Palme prize, named for the Social Democrat who led his country for 11 years and was mysteriously gunned down in a Stockholm street in 1986 after leaving the cinema. Playwright and political dissident Václav Havel won in 1989, soon before becoming president of Czechoslovakia, Danish novelist Carsten Jensen won in 2009 and the Italian journalist and author of Gomorrah Roberto Saviano won in 2011.

Le Carré will receive his award at a ceremony in Stockholm on 30 January.

Filed under 2020, author, author tribute, awards

Source: Celebrity Killed The Radio Star | You and Me, Dupree

One of the most moving, most significant, most powerful books I’ve read over the last few years is mainly made up of illustrations. It’s the remarkable ALL THE ANSWERS, a “graphic memoir” by Michael Kupperman, and I strongly urge you to give it a spin.

The author is not new to me: I published Michael Kupperman’s first book, SNAKE ’N’ BACON’S CARTOON CABARET, nearly twenty years ago. We had noticed his work in such publications as the Oxford American, and every time we saw another cheerily demented comic strip we wound up wiping tears of laughter from our faces. Mike has a straight-laced, almost retro drawing style that you can tell a mile away (by now, others are obviously trying to imitate it). But the cultural melange roiling around in his brain is unique, charming and dangerous. He loves old Hollywood, old media (heavy-breathing magazine ads from the Thirties and Forties are a huge inspiration), mass marketing to innocents, deliberately absurd juxtapositions — you can’t possibly get ahead of him before you turn the page.

Either you love this stuff to death or you want to throw it across the room. Some people at the publisher where I worked were far from smitten, but to their credit they said, we don’t get it, but we get that you get it. I got the green light and set out to find the guy who signed his work “P. Revess” by calling those magazines and asking, where do you send the checks? Turned out they headed right here, to New York City, to a guy named “Michael Kupperman.” When I called him to ask about his interest in possibly doing a book, I detected a hint of suspicion, the do-you-have-Prince-Albert-in-a-can type. But I proved my bona fides and we made a deal. No agent, no nuthin.

The book sold modestly but steadily (it’s still in print after all this time, which is an achievement on its own), but more important, it introduced Mike to a growing and influential audience. Art directors loved his funky visual style: I started to see his spot illustrations in unexpected places like the New Yorker. One week he did the cover and interior color illos for the lead story in an issue of Fortune. He was all over the place outside the comics field for a while.

He was also getting noticed in the world of comedy. Andy Richter, Conan O’Brien’s original sidekick, was such an early fan that he gave us a quote for our book cover. Conan himself called Mike “probably one of the greatest comedy brains on the planet.” Robert Smigel, who is also probably one of the greatest comedy brains on the planet, heartily agreed and adapted some wild stuff for his TV FUNHOUSE, and Michael Kupperman was officially hip. There’s since been more tv, more illustration, more comics, and in 2013 Mike won the Eisner Award, comics’ highest honor, for a fevered, off-the-scale-hilarious story about the 1969 moon landing in his book TALES DESIGNED TO THRIZZLE.

I’ve been following Mike’s career as best I could in the years since we worked together. I’m proud of him. But nothing prepared me for this latest dazzler. It comes from someplace deep inside the artist, an excruciatingly personal corner where he hasn’t allowed us before. As the flap copy calmly states, “This is his first serious book.”

Nearly every creative person I’ve ever encountered, myself certainly included, loves it when s/he is credited by name. A couple times I casually asked Mike why he signed a pseudonym instead and never got a straight answer. Maybe this book provides a clue. I didn’t know it, but there was a time when “Kupperman” was one of the most famous surnames in America. It belonged to an unwitting pioneer of celebrity culture, a child star whose popularity was launched and exploited by the mass medium of radio. This was Michael’s father, Joel Kupperman. He was a Quiz Kid — probably the best known Quiz Kid of them all.

Joel was a “child prodigy” when that term was new. He scored better than 200 on the Stanford-Binet test when he was only six years old. His specialty was doing complex mathematical calculations in his head; he was also a maven at trivia and remembered nearly everything he read. He was a perfect fit for QUIZ KIDS, a radio program created by broadcasting executive Louis G. Cowan (the author calls him “almost certainly the smartest person in this book”) in which children answered questions sent in by listeners. Joel’s first appearance was in 1942; he was five.

Today Joel is a grandfather. He spent fifty years teaching and writing books about philosophy. He has been a good man, neither an abuser nor philanderer, but to his son lamentably distant. Now, before Joel succumbs to the dementia that has just been diagnosed, the young Kupperman wants to open a subject which his father has compartmentalized and never discussed: the traumatic years on QUIZ KIDS which basically stole his childhood, tormented him as he grew out of single-digit cuteness and the show migrated to television, and caused him to recoil from the whole experience.

The complexities which intertwine to form this saga include the state of mass media in the mid-twentieth century, Joel’s stern and smothering stage mother, the role of anti-Semitism on QUIZ KIDS, the high price of fame, and most searingly, the poignant real-life relationship between a wounded father and his son, who is by now raising his own young boy. These strands dart and weave and intersect in magical ways: ALL THE ANSWERS turns on a dime from humor to heartbreak.

It looks simple, but looks are deceiving. The pages are trimmed to 6-by-9, just like a book full of words. It’s drawn in black-and-white (like the book we did together). The illustrative style is Kupperman-clean, with slightly more ornate chapter-heading ”splash pages,” and show off how the artist can conjure familiar people from real life with just a few economical lines (a secret cache of scrapbooks assiduously kept by Joel’s mother provides all the contemporary source material needed). The first-person narration is active, impassioned, haunting and honest, a world away from the hyperventilating wisenheimer of gonzo Kupperman comics. The text in ALL THE ANSWERS is so clear that it serves to emphasize the rich subtext. Ideas, emotions, relationships, issues, injustices, yearnings — they all pop off the pages in deeply human ways. It appears to be hand-lettered, though I bet there’s a computer involved by now, but this isn’t a comic book. It’s exactly what it claims to be: a graphic memoir. The closest cousin I can think of is Alison Bechdel’s FUN HOME, but this feels even more basic and vital, and you can’t stop comparing the World War II years — QUIZ KIDS’s golden age — with our culture today. As you read, Michael Kupperman’s very personal world expands to encompass your own.

Artists are supposed to startle and surprise us. Boy, did this book deliver. I didn’t know Michael Kupperman had it in him. I’ll be thinking about this for a long time, especially while reading this talented man’s next outrageous bit of goofiness, which I hope comes along very soon. (He’s got an agent now.) It’ll be even more fun now that I know the guy a little better.

Sing the truth

Share this:

Leave a comment

Filed under 2025, author, author commentary

Tagged as novel, poem, salman rushdie, truth, writing